Indian Act and the Pass System

No rebel Indians should be allowed off the Reserves without a pass signed by an I.D. official. The dangers of complications with white men will thus...

The federal government’s Indian Act policies for Indians or First Nation(s) people during the nineteenth century were primarily concerned with assimilation. One aspect of the assimilation process was the renaming of the entire First Nation population, partly to extinguish traditional ties and partly because Euro-Canadians found many of the names confusing, difficult to pronounce and went against assimilation objectives - it was feared that leaving them with their traditional names would take away the motivation to assimilate.

We are always very careful to respect cultural diversity when writing about broad-scope topics in order to not give the impression that all First Nation communities share the same attributes.

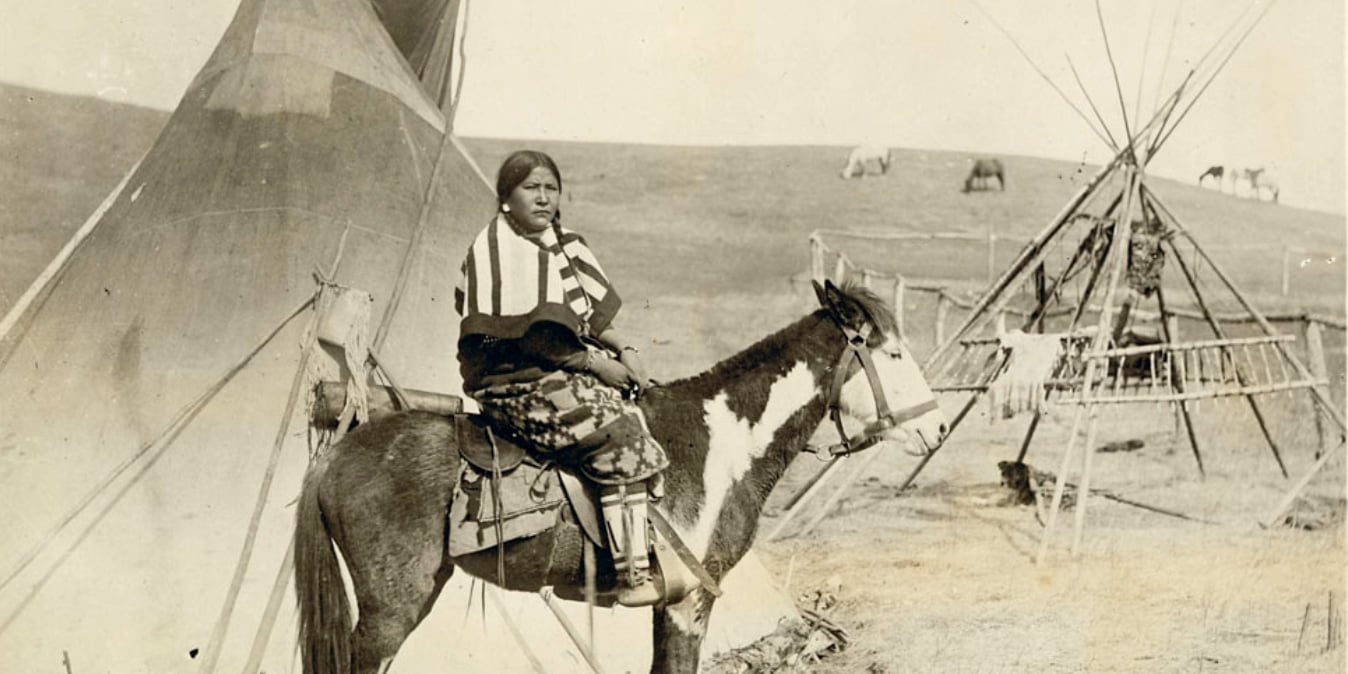

Traditionally, First Nations people had neither a Christian name nor a surname - they had hereditary names, spirit names, family names, clan names, animal names and or nicknames to name but a few. Hereditary names, in some cultures, are considered intangible wealth and carry great responsibility and certain rights and have been described as being analogous to royal titles such as “The Duke of Edinburgh”. In many cultures, the birth name was just for that stage of life, and additional names were given to mark milestones, acts of bravery or feats of strength. None of the great heritage, symbolism or tradition associated with names was curated, recognized or respected during the renaming process.

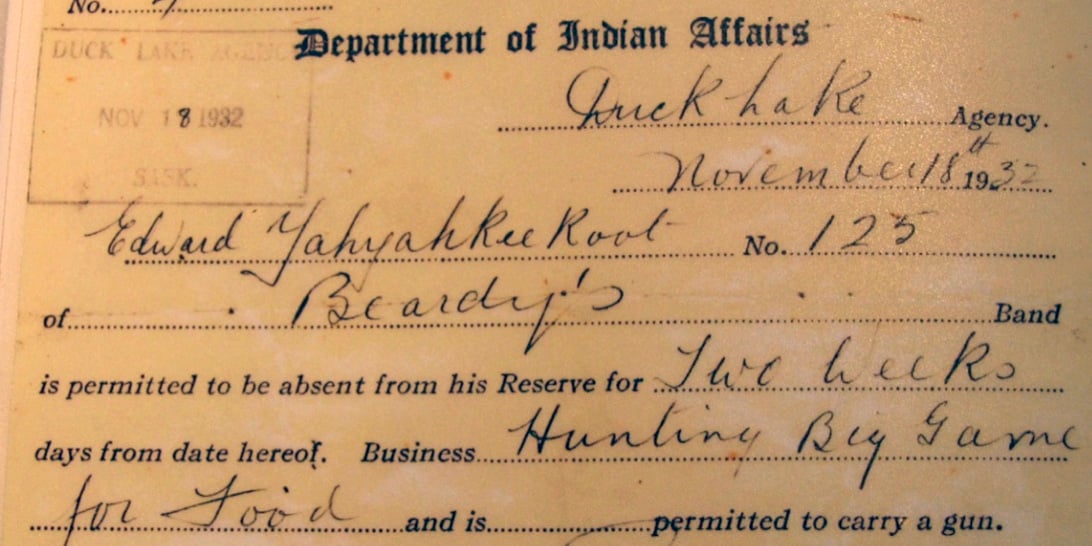

Traditional naming practices did not make sense to the Indian agents, charged with recording the names of all people living on reserves. The diversity of names and naming practices also made record-keeping difficult. While there was not a uniform approach adopted by all Indian agents to the renaming process, generally the agents assigned each man a Christian name and more often than not, a non-native surname. Women were given Christian names and assigned the surname of their fathers or husbands.

The Indian agents on the west coast of Canada often used biblical names from different religious denominations, repeating them as they worked their way through their jurisdiction, which explains the frequency of unrelated families that share common last names. Or, they used their own names. As all agents were male, very few if any, female names were used.

This is how the process would have unfolded: I would be asked my name, I would say “k’acksum nakwala”, and they would have written down “Bob Joseph”. Often I am asked if I am related to the Josephs from the Squamish First Nation, to which I usually reply “No, but I’m sure we had the same Indian agent”. [1]

It’s ironic that the First Peoples of Canada have surnames that only date back a few generations. It is certainly not the case for ancestral names, which date back to Creation.

Traditional names, naming ceremonies and many other cultural traditions were discouraged and in some cases, outlawed. Indian agents and missionaries worked under the mandated assumption that all First Nations would, through one policy or another, eventually abandon their traditions and culture, and blend into the prevailing Euro-society, thereby eradicating the “Indian problem”. The Deputy Minister of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott wrote, in reference to the assimilation policies,

The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government... Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.

Today, it is becoming more common to see First Nation individuals proudly carry their ancestral or spiritual names in conjunction with family names such as “Kekinusuqs, Dr. Judith Sayers”, former chief of the Hupacasath First Nation, and “Shawn A-in-chut Atleo”, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released its report and 94 Calls to Action, one of which relates to reclaiming traditional names.

17. We call upon all levels of government to enable residential school Survivors and their families to reclaim names changed by the residential school system by waiving administrative costs for a period of five years for the name-change process and the revision of official identity documents, such as birth certificates, passports, driver’s licenses, health cards, status cards, and social insurance numbers. [2]

There is also a growing movement in Canada to reclaim traditional community names, as recently done in Alberta. The town of Hobbema reverted officially on December 31, 2013, to its original Cree name of Maskwacis, which means “Bear Hills”.

If naming policies is your area of interest, please read "The Relationship between Indigenous Peoples and Place Names"

[1] excerpt from 4th edition Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® available for purchase online

[2] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Featured photo: Unsplash

No rebel Indians should be allowed off the Reserves without a pass signed by an I.D. official. The dangers of complications with white men will thus...

When an Indian woman marries outside the band, whether a non-treaty Indian or a white man, it is in the interest of the Department, and in her...

It’s tax time and that means tax pain, as the television commercials say. Tax time is also the time of year that one hears the common myth that...