Indigenous Language Immersion

Indigenous languages the world over are in jeopardy. So much so that the United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages...

5 min read

Bob Joseph February 15, 2019

Of the most spoken languages in the world, English is third after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. But English is the most commonly spoken second language in the world and is the most common language used on the internet. As accessibility to the digital world expands, so too will the spread of English as a second language.

This will impact all languages but those languages already endangered will be the most severely impacted as young people become fluent in the language of the internet and not their home language; the impact will be compounded through the following generations.

Many Indigenous languages are endangered globally and the rate of loss is estimated at one language every two weeks.

Between 1950 and 2010, 230 languages went extinct, according to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Today, a third of the world’s languages have fewer than 1,000 speakers left. Every two weeks a language dies with its last speaker, 50 to 90 per cent of them are predicted to disappear by the next century. [1]

As for Indigenous languages in Canada, some are thriving whereas others, such as Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca are on the brink of extinction. According to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger project, “three-quarters of Indigenous languages in Canada are “definitely,” “severely” or “critically” endangered. The rest are classified as “vulnerable/unsafe.” [2]

Well, it’s not entirely due to the encroachment of the digital world. The root of the decline lies in the Indian Act and is compounded by demographics and the internet.

During the era of residential schools, it is estimated that 150,000 children were removed from their families and communities and placed in residential schools. While interned in the schools the children were forbidden to speak their home language and if they did they often were subjected to horrific forms of punishment. When the children returned home for holidays, they were frequently too traumatized to converse in their language. And when they had children of their own, they frequently did not teach or encourage them to speak their home language, in part because their fluency had been impacted, in part because they feared their children would suffer the same punishment, and in part because they believed their children needed fluency in the dominant language. Multiply that scenario through a few generations and we have a 2016 statistic of just 16 percent of Indigenous people (1,673,785) able to speak an Indigenous language.

Language is the foundation of a culture. For Indigenous oral societies, words hold knowledge amassed for millennia. A language also holds the stories, songs, dances, protocols, family histories and connections. Languages also often hold the community’s customary laws that were eroded by the policies of the Indian Act. As many communities move towards a return to self-government, this loss of laws and systems of governance means some communities don’t have that knowledge to draw upon.

When a language dies so does the link to the cultural and historical past. Without that crucial connection to their linguistic and cultural history, people lose their sense of identity and belonging.

Indigenous Peoples have been observing and talking about their environment since time immemorial. All of that knowledge, held in the language, is an invaluable source of information about the history of the natural environment, climate, plants, and animals. It is an irretrievable body of knowledge. Science, medicine, governments and resource planners all rely in part on Indigenous traditional knowledge and are all impacted when that irreplaceable storehouse of traditional environmental knowledge is gone. Each language that dies equals the loss of a cultural treasure.

Nunavut, which has three official languages: the Inuit language (Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun), English and French, is the only territory with a language protection act. The Inuit Language Protection Act, passed in 2008, aims to increase the number of speakers, and revitalize and protect the Inuit language. Under the Act, Inuit have the right to work for the Government of Nunavut in their own language, municipalities must offer services in the Inuit language, and private businesses are required to display Inuit text as prominently as English and French.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s released its 6-volume report on the residential schools and what Canada and Canadians needed to do for reconciliation. The Calls to Action included #14 for an Aboriginal languages act and #15 for an Aboriginal languages commissioner.

The state of Indigenous languages is such a concern that UNESCO declared 2019 The Year of Indigenous Languages. Here in Canada, a week after the Year of Indigenous Languages was launched, the federal government tabled the Indigenous Languages Act.

In January 2019, the House of Commons witnessed a historic moment when then-Member of Parliament Robert Falcon Ouellette, while speaking in Cree, had his speech simultaneously translated. That’s a first! The House of Commons now offers simultaneous translation in some Indigenous languages.

Circling back to the advancement of the digital world having an impact on Indigenous languages, the digital world may also play an important role in saving languages. Language and keyboard apps are being developed that help users learn common words and phrases. First Peoples Cultural Council on their FirstVoices page has apps available to help reclaim and revitalize 13 Indigenous languages.

Efforts to preserve and revitalize Indigenous languages are a race against time as fluent speakers pass on. But, there are actions and developments underway to preserve and revitalize some Indigenous languages.

Vocalize your support for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s call to action for language by reading the Indigenous Languages Act and staying abreast of the response to the Act. Are Indigenous Peoples supportive of the Act? Do they have concerns? We will be sharing news articles on the Act so consider following me on social media. Links to my social media platforms are in the grey banner at the bottom of this page.

Here’s the full call to action on language:

Language and culture

13. We call upon the federal government to acknowledge that Aboriginal rights include Aboriginal language rights.

14. We call upon the federal government to enact an Aboriginal Languages Act that incorporates the following principles:

i. Aboriginal languages are a fundamental and valued element of Canadian culture and society, and there is an urgency to preserve them.

ii. Aboriginal language rights are reinforced by the Treaties.

iii. The federal government has a responsibility to provide sufficient funds for Aboriginal-language revitalization and preservation.

iv. The preservation, revitalization, and strengthening of Aboriginal languages and cultures are best managed by Aboriginal people and communities.

v. Funding for Aboriginal language initiatives must reflect the diversity of Aboriginal languages.

Learn the traditional name of where you live

Learn a greeting in the traditional language of where you live

Challenge family members and colleagues to learn some phrasing in the traditional language of where you live or work

Learn an Indigenous language

To learn more about Indigenous history, culture and language, our Working Effectively With Indigenous Peoples® training is a great place to start.

[1] Nina Strochlic, The Race to Save the World's Disappearing Languages, National Geographic April 2018

[2] Nick Walker, Mapping Indigenous languages, Canadian Geographic, Dec 2017

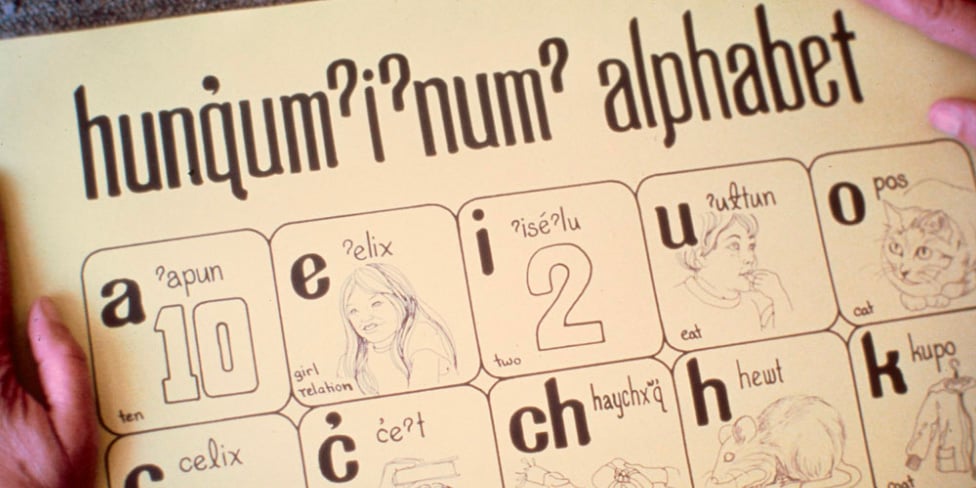

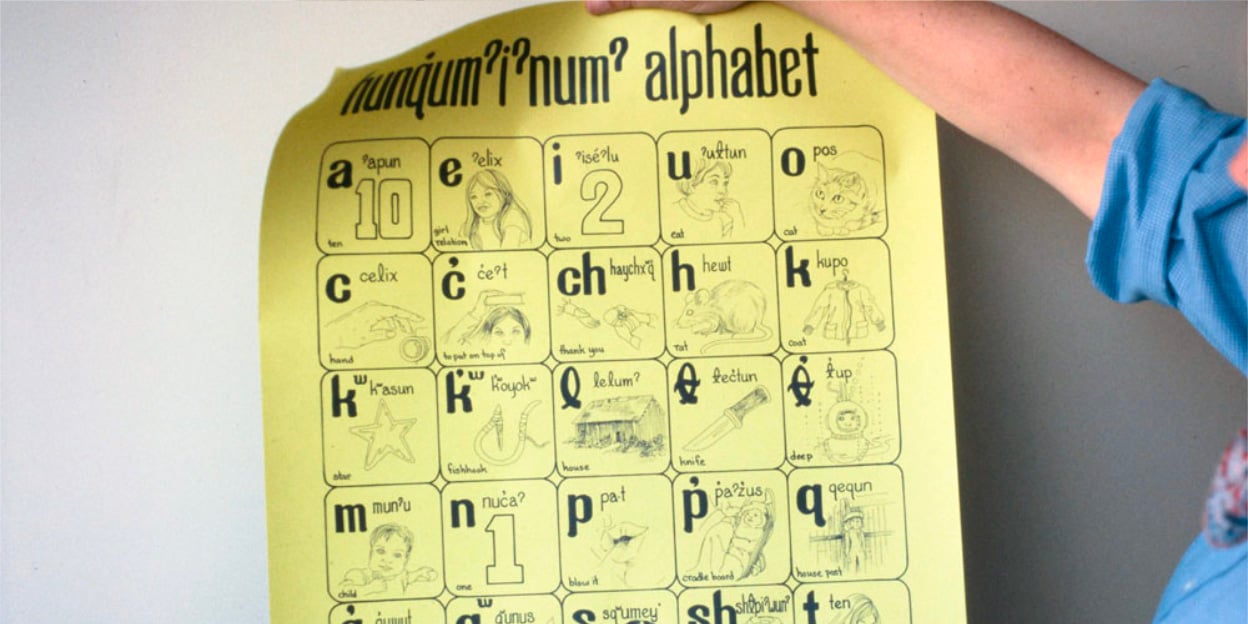

Featured photo: Hun¿qum¿i¿num¿ alphabet poster, a dialect of Halkomelem, Coast Salish. Photo: George Mully / George Mully fonds / Library and Archives Canada.

Indigenous languages the world over are in jeopardy. So much so that the United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages...

The COVID-19 pandemic could be the single greatest threat in this generation to the continuity of Indigenous cultures and the preservation of...

Indigenous languages are struggling to survive. With the number of Indigenous language speakers on the decline, some of these languages are on the...