Indian Residential Schools: A Collection of Articles

On this blog, we have written a number of articles on residential schools, and the impacts and outcomes of those schools on First Nations...

Schools.

Indian Act. R. S., c. 43, s. 1. 1884

11. The Governor in Council may make regulations, which shall have the force of law, for the committal by justices or Indian agents of children of Indian blood under the age of sixteen years, to such industrial school or boarding school, there to be kept, cared for and educated for a period not extending beyond the time at which such children shall reach the age of eighteen years.

And so it began... the most aggressive and destructive of all Indian Act policies. Residential schools brought immeasurable human suffering to the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, the effect of which continues to reverberate through generations of families and many communities. Other policies were harsh but could be worked around. They banned the potlatch so practitioners went underground to hold ceremonies; they pushed people onto small reserves but they still were with family. But when they took the children that was unbearable.

The goal of the schools was to “kill the Indian in the child” but sometimes the child themselves died - 6,000 of the 150,000 who attended the schools between the 1870s and 1996 died or disappeared. The numbers are not precise because neither the schools, the churches that managed the schools, nor the Indian agents kept accurate records.

When the federal government signed the 11 numbered treaties (the first one signed in 1871), it assumed responsibility for the education of the Indigenous people of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, as well as portions of Ontario, British Columbia, and the Northwest Territories. First Nation signatories to the treaties realized that life as they knew it was seriously impacted by the influx of Europeans and wanted the children to have an education so they could take part in the new wage economy - they did not envision what lay ahead.

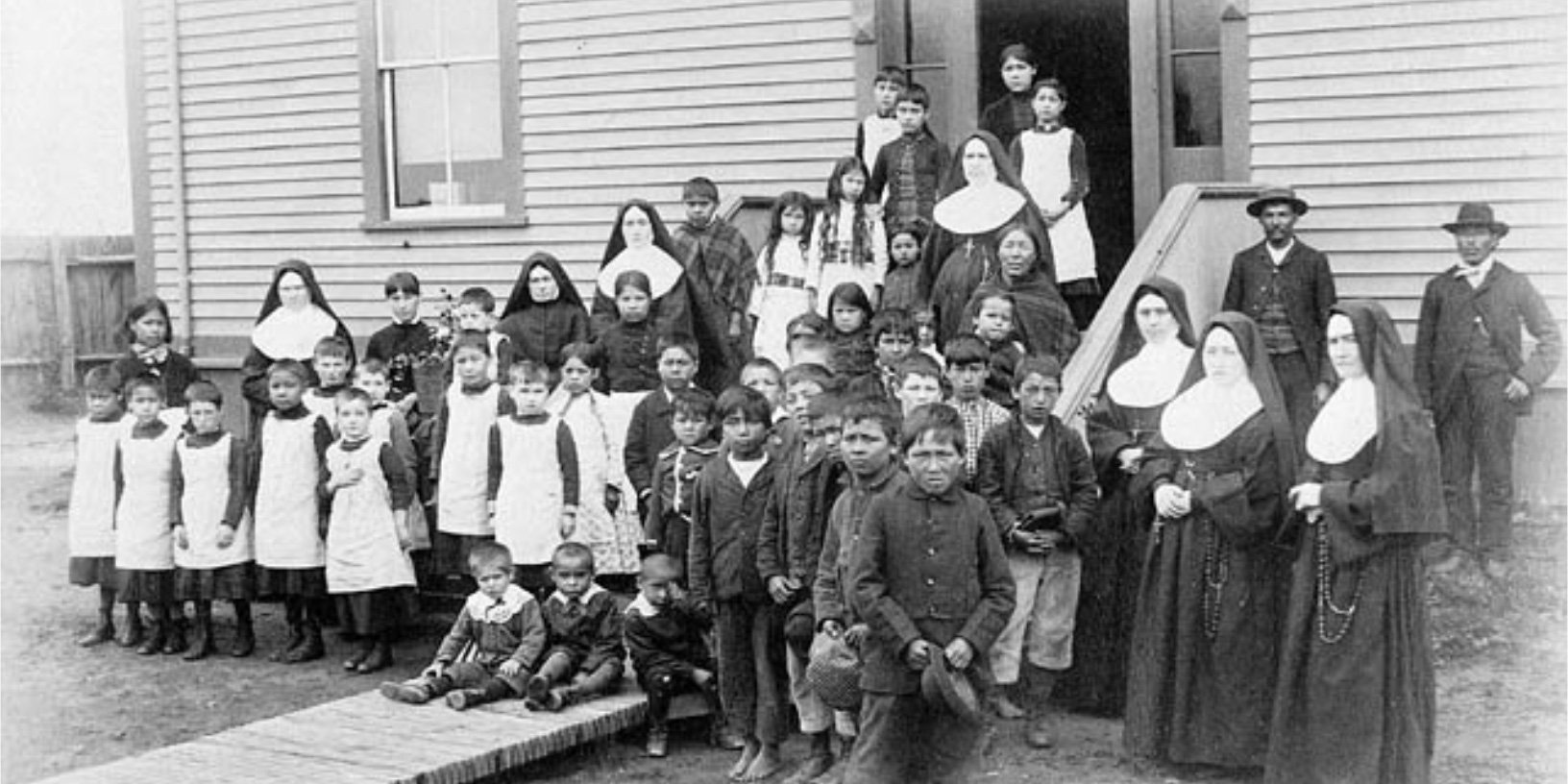

Prior to the 1876 Indian Act, education was provided at day schools built on reserves for the children to attend and begin their assimilation into settler society but issues with low attendance impeded this plan. The education policy was revised after government officials studied how the American government managed the education of native children.

Sir John A. Macdonald, to the House of Commons in 1883:

When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men. [2] Canada, House of Commons Debates (9 May 1883).

The revised policy abandoned on-reserve schools in favour of off-reserve, dormitory-style, industrial schools. This new system was considered favourable by the government because it separated the children from their parents thereby allowing for the full indoctrination of the children into Christian beliefs and customs - to kill the Indian in the child.

In 1920, the Act was amended to combat low attendance by making it compulsory for status Indian children to attend residential schools, with consequences for those who hid their children. If children were not readily handed over, the Indian Act gave power to the Indian agent to enter the family dwelling and seize the children, often with the help of the local constabulary or by the constabulary alone. Parents or guardians who tried to hide the children were liable to be arrested and or imprisoned.

A(3) Any parent, guardian or person with whom an Indian child is residing who fails to cause such child, being between the ages aforesaid, to attend school as required by this section after having received three days= notice so to do by a truant officer shall, on the complaint of the truant officer, be liable on summary conviction before a justice of the peace or Indian agent to a fine of not more than two dollars and costs, or imprisonment for a period not exceeding ten days or both, and such child may be arrested without a warrant and conveyed to school by the truant officer: Provided that no parent or other person shall be liable to such penalties if such child, (a) is unable to attend school by reason of sickness or other unavoidable cause; (b) has passed the entrance examination for high schools; or, (c) has been excused in writing by the Indian agent or teacher for temporary absence to assist in husbandry or urgent and necessary household duties. [3]

You will notice that the child could be excused if they were diligently employed in the schools’ farms or “household duties” i.e. cooking and cleaning. The children often worked in the fields to raise products for sale to offset costs and cooked or cleaned more frequently than they had lessons in classrooms.

Being absent for traditional pursuits was forbidden. Actually, every aspect of their former lives was forbidden - the children were not allowed to speak their language, practice their traditions, dress in their own clothing and could only visit their families during Christian holidays, and only if the parents were compliant with certain rules.

The schools, primarily managed by Anglican, Roman Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian and United churches and a government that was desperate to shed the financial responsibility of First Nations, were chronically underfunded. To augment the finances of the schools, the Act included a statute that allowed the government to collect any treaty annuities due the children and use the money for the maintenance of the school that the child attended. The buildings were drafty and unsanitary; food for the children was insufficient and often rotten. The schools were also breeding grounds for diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza and the children, suffering from the trauma of the absolute loss of everything familiar in their lives, had severely impacted immune systems which left them vulnerable to disease. “Fear, anxiety or depression prompted by a change in environment, lifestyle, or values adversely affect the body's immune system.” [4]

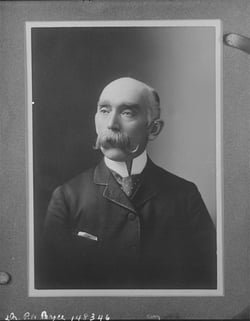

The high death rate of the children was a concern of the Chief Medical Officer for the Departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs, Peter Bryce. Bryce released his Report on the Indian Schools of Manitoba and the North West Territories in 1907. The report provided grim facts regarding the devastating effects of tuberculosis on the children (24 percent of the children, within the first 15 years, had died) [5] and recommendations on how to improve the standards of the schools to stem the spread of the disease both in the schools and the home communities of the students.

The Department of Indian Affairs, however, would not publish his recommendations presumably because they entailed costly renovations to school facilities and a full re-examination of the native residential education system. [7]

Most of Bryce’s recommendations were rejected by the Department of Indian Affairs (the Deputy Superintendent-General at the time was the infamous Duncan Campbell Scott) as too costly and not aligned with the government’s policy for rapid, affordable assimilation.

According to a national magazine, the same year Bryce made his report "Indian boys and girls are dying like flies... Even war seldom shows as large a percentage of fatalities as does the education system we have imposed on our Indian wards." [6]

Bryce was committed to honouring his role in the government’s obligation under both the British North America Act (BNA) and the numbered treaties to protect and educate First Nation children, later wrote The story of a national crime: being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada; the wards of the nation, our allies in the Revolutionary War, our brothers-in-arms in the Great War.

Residential schools are not ancient history - the last one closed in 1996. Attendance was mandatory until 1969. The intergenerational impacts will continue to be experienced for many generations to come.

There are many aspects and outcomes of the residential school system beyond those mentioned in this article. If you found this article on the Indian Act, residential schools and tuberculosis interesting but want to learn more, here are some suggestions for additional information:

[1] Indian Act. R. S., c. 43, s. 1. 1884

[2] Canada, House of Commons Debates (9 May 1883)

[3] Indian Act. c.50, s.1 1927

[4] Leonard A. Sagan, The Health of Nations: True Causes of Sickness and Wellbeing

[5] Peter Bryce, The story of a national crime: being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada; the wards of the nation, our allies in the Revolutionary War, our brothers-in-arms in the Great War

[6] Saturday Night magazine November 23, 1907

[7] Meagan Sproule-Jones, Crusading for the Forgotten: Dr. Peter Bryce, Public Health, and Prairie Native Residential Schools

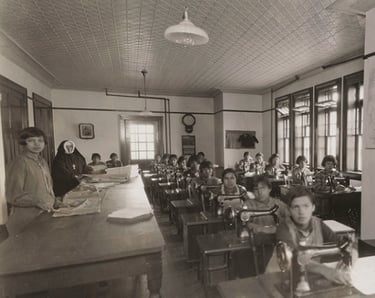

Featured photo: Class portrait of male students, nuns, a priest and school personnel at St. Anthony's Indian Residential School, Onion Lake, Saskatchewan, ca. 1950. Photo: Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development / Library and Archives Canada / Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds / e011306856

On this blog, we have written a number of articles on residential schools, and the impacts and outcomes of those schools on First Nations...

In 1844, the Bagot Commission of the United Province of Canada recommended training students in “…as many manual labour or Industrial schools as...

This article includes a video of a conversation I had with my father Chief Robert Joseph, O.C., O.B.C., about his first day at residential school and...