Smudging to Indigenous Protocol - Our Top 10 Articles in 2017

In 2017, we had just over 816,000 visitors to our blog Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® looking for information on a wide variety of...

The Bostonian Robert Kemp, on the brig Otter just north of the Queen Charlotte Islands in December 1810, reported that "the Natives are all infected with the Land Scurvy which Renders them Completely Incapable of Hunting[.] this Coast is as Silent and Solitary as the House of death and I wish that I was Clear from it. [1]

Throughout the Americas, Indigenous contact with Europeans was soon followed by drastic declines in Indigenous populations. With no natural immunity to diseases introduced by the Europeans, Indigenous Peoples were decimated by waves of epidemics of smallpox, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, influenza and measles. [2] The smallpox virus, which came not so much as waves but as tsunamis, decimated the coastal First Nation population not once, but at least twice. Smallpox devastated Indigenous populations in other regions of the country as well but here we focus on the impact of smallpox on First Nations on the West Coast.

There isn’t a definitive estimation of the Indigenous population of British Columbia prior to contact with Europeans.

Prior to contact with Europeans, the area now known as British Columbia had one of the densest and most linguistically diverse populations within what is now Canada. It is estimated that one third of the pre-contact population of Canada resided within British Columbia. Pre-contact population estimates for BC vary widely with some estimates ranging from a conservative 200,000 to more than a million. Earlier estimates of 80,000 have now been discredited as far too low.

Oral traditions of many First Nations give a much higher original population than what is generally accepted by western academics, even now. From oral history and ongoing research it is clear that the European diseases that ravaged the Central and South American populations spread in advance of actual contact to First Nations in BC. Therefore early explorers and traders who considered the populations quite low were witnessing Nations who had already experienced drastic decreases. What is clear to everyone is that the population was of ancient origins, large, varied, and relatively healthy prior to the introduction of European diseases. [3]

There are differing opinions about the number and source of the earliest arrival of the smallpox virus and ensuing epidemics. Some historians say there was one in the north in the 1770s, introduced by sea and another in the south in 1781-82, introduced by land. What everyone agrees upon, however, is that the Indigenous population had no immunity to the virus. The close confines of the winter homes provided the ideal footing for the virus to devastate entire communities. People died at such a rate that it became impossible to bury the dead according to traditions which led to mass burials, and eventually, those too became unmanageable, and the dead were left where they died. Community members who fled to avoid the sickness took it with them thereby spreading the infection.

Gradually, communities rebuilt and the population grew and traditions were revived. Life as the coastal communities had known it would never be the same as by this time European forts were being established and an active trading relationship was developing.

But then, in March 1862, less than one hundred years later, the virus was re-introduced. There is much more information available about this second smallpox epidemic.

At the time, Victoria is estimated to have had a population of 2,500 - 5,000 (non-Indigenous). In addition, it is estimated that there were 1,600 local First Nations who lived near Victoria, plus another 2000 in encampments on the outskirts of town. Those in the encampments were from a number of northern communities, some as far away as Alaska.

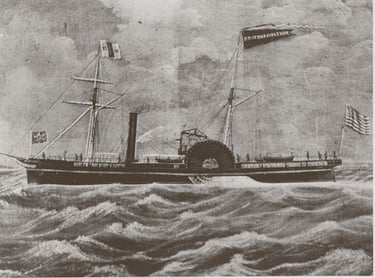

On that fateful day in March, when the Brother Jonathan sailed into Victoria harbour from San Francisco, for a one-night layover, she carried not only hundreds of boisterous gold-seekers drawn to the Cariboo gold rush but also one silent, lethal passenger. For twenty-four hours, the passengers made the most of their time in Victoria, which included interactions with the First Nation encampments, before they re-boarded and departed.

Just over one month later, the encampments and some of the local First Nation communities were overwhelmed by the disease and there was fear within the citizens of Victoria that they too would be overrun by the virus, despite having access to the vaccine. In response to that fear, the Commissioner of Police, Joseph Pemberton, began ordering those in the encampments to leave, knowing full well what it meant to all they interacted with. Then that order was extended to all infected First Nations on the southeastern end of Vancouver Island. And then this:

Pemberton went further than just demanding that the Indians leave. On June 11, 1862, the Police Commissioner and a group of policemen forced about 300 men, women, and children camped near Victoria to return to their northern homeland. The gunboat Forward (Captain Lascelles), took a 15-day trip to Fort Rupert towing 26 canoes full of natives. Included were 20 canoes of Hydahs [Haida], five canoes of other Indians from the Queen Charlotte Islands, and one canoe of Stickeen [Tlingit] Indians. [4]

It’s estimated that, prior to the 1862 smallpox epidemic, there were about 30,000 First Nations living on the coastline of BC, post-epidemic that number drops to 15,000. But, sadly, the devastation was not restricted to the coast. Through trade and travel, the smallpox virus was spread to almost every First Nation community in the province.

The impact of the epidemic was devastating beyond the number of people who died. Their cultures, which had evolved since time immemorial, were severely interrupted, not once but twice. Despite the deep losses, once again, the nations began the slow process of rebuilding communities, and reviving cultures and traditions, although this time, as the communities rebuilt, they were doing so under the regime of the Indian Act of 1876.

[1] Social Power and Cultural Change in Pre-Colonial British Columbia, Cole Harris

[2] Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples®, 4th edition, Robert Joseph and Cynthia F. Joseph

[3] First Nations Health Authority

[4] Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 among Northwest Coast and Puget Sound Indians, Greg Lange

Featured photo: Shutterstock

In 2017, we had just over 816,000 visitors to our blog Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® looking for information on a wide variety of...

We are in uncharted waters these days as countries around the world scramble to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. While we are all at risk and all...

Following every training session we ask learners if they would kindly take the time to fill in a survey about the training. We find these surveys...