6 Guidelines for Projects Involving Traditional Indigenous Knowledge

Traditional Indigenous knowledge (TK) and traditional resources have been managed by Indigenous communities since time immemorial. The arrival of...

4 min read

Bob Joseph May 15, 2018

There are more and more articles in the news about the value of Indigenous traditional knowledge being taken into account in climate change studies, environmental assessments, wildlife management, and plant species studies. That has not always been the case. Historically, traditional ecological knowledge was largely ignored by western ecological science practitioners.

In this article, we take a look at the many factors that had to be in place to support the recognition of Indigenous traditional knowledge (ITK) from obscurity to being considered a valuable asset in environmental studies. At the time of this writing, May 2018, it is still not mandatory in the environmental assessment process.

Back in 1974, Justice Thomas Berger was commissioned by the Canadian government to

...assess the potential environmental and socio-economic impacts of the proposed McKenzie Valley Pipeline, Berger held public consultations in 35 Indigenous communities to hear the various concerns over the proposed project from local Indigenous residents. Berger brought both the interests and the valued knowledge of Indigenous inhabitants to the attention of the Government of Canada, recommending that the project be suspended for 10 years to negotiate Indigenous land-claim agreements in the McKenzie Valley. It can be argued that the McKenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry “set a precedent of consultation with local Aboriginal people”, allowing for the knowledge and values of Indigenous residents to be effectively communicated to environmental decision-makers. [1]

Keep in mind that Justice Berger’s precedent-setting consultations took place prior to Aboriginal Peoples having constitutionally protected rights in Canada, and before there was a legislated duty to consult. It was the beginning of new world order in terms of considering the impact of resource development projects on Indigenous Peoples.

Legislatively, the shift in attitude concerning Indigenous, or Aboriginal, rights began in the 1980s. Why then? Well, there were some pretty significant events, nationally and internationally, for Indigenous Peoples in the 1980s.

In Canada, the constitution was repatriated in 1982 to include s. 35which recognized Aboriginal rights:

35(1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal people in Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

(2) In this Act, “Aboriginal Peoples of Canada “includes the Indian, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada.

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1), “treaty rights” includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

(4) Notwithstanding any other provision of this act, the aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in subsection (1) are guaranteed equally to male and female persons. [1]

Constitutionally protected rights provided the necessary foundation for Aboriginal Peoples to take legal action to establish title. The 1980s was an era of significant rulings which included the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) ruling that the “federal government had “fiduciary responsibility” for Aboriginal people - that is, a responsibility to safeguard Aboriginal interests. This duty placed the government under a legal obligation to manage Aboriginal lands as a prudent person would when dealing with his/her own property.” [2]

Also, during this time, negotiations began on some modern treaties and self-government agreements. Efforts were underway in the north to establish the territory of Nunavut, which when finalized in 1999, gave 35,000 Inuit control over the government.

Internationally, in 1982, a study on systematic discrimination was released by UN Special Rapporteur of the Sub-commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities José R. Martinez Cobo. The study was the catalyst for, several decades later, the 2007 signing of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Concurrently, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) began gaining ground in boardrooms which in turn ushered in the concept of ethical investing. CSR is not mandated in Canada, and there are widely varying versions of what a company considers CSR but it has placed expectations on governments and resource development companies.

Yes, greenwashing can be a risk, but as time goes on, stakeholders from NGOs and pressure groups to customers and investors – are all becoming more adept at knowing the difference between PR spin and [corporate responsibility] performance. It is not so easy to pull the proverbial wool over people’s eyes anymore. [3]

This decade saw some opportunities for ITK to finally be respected for the body of knowledge it represents. Despite being bolstered by the SCC ruling in Delgamuukw and Gisda’way which established that “The fiduciary duty between the Crown and Aboriginal Peoples may be satisfied by the involvement of Aboriginal Peoples in decisions taken with respect to their lands” [4] the impact of that ruling was not considered in the 1992 Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (assented to in 1995)

Through another series of significant court decisions “Aboriginal people gained recognition of their harvesting rights, for both subsistence and, in some instances, commercial purposes. The Supreme Court of Canada established a “duty to consult and accommodate” in their decisions on Haida and Taku River, both in 2004, for governments (which typically delegated the responsibility to corporations wishing to pursue resource developments on indigenous territories).” [5] The ability to harvest is directly connected to the health of the environment.

And then in 2003, huge progress toward recognition was made when the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act was amended to include:

16.1 Community knowledge and aboriginal traditional knowledge may be considered in conducting an environmental assessment. [6]

But, sadly, s.16.1 was repealed in 2012, which undid decades of progress.

Now, in 2018, there is the proposed Impact Assessment Act.

The proposed Impact Assessment Act, which was introduced in January following 14 months of consultations with the Indigenous community, companies, provinces and territories and environmental groups, is designed to replace the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act.

Its more comprehensive assessments would show how a company’s proposed project could affect the environment, health, society and the economy, as well as how the development would impact Indigenous people over the long term. [7]

There are concerns about this proposed Impact Assessment Act such as no requirement to cross-reference the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

And that is where the inclusion of Indigenous traditional knowledge in Environmental Assessments stands.

[1] Nigel Vidler and Elias Elhaimer Indigenous Traditional Knowledge in Canadian Federal Environmental Assessment, Submission to the Expert Review Panel, 2016

[2] Bob Joseph and Cynthia F. Joseph, Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples®, 4th edition, Indigenous Relations Press, 2018 p 40

[3] Corporate Social Responsibility in the Canadian Mining Sector: Rhetoric, Ethics, and the Economy by Heidi Wudrick B.A., University of Victoria, 2009 (KMPG, 2013, p. 10)

[4] Delgamuukw v. British Columbia [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, para. 168

[5] Ken Coates and Carin Holroyd, Indigenous Internationalism and the Emerging Impact of UNDRIP on Aboriginal Affairs in Canada, Internationalization of Indigenous Rights UNDRIP in the Canadian Context, Special Report, 2014

[6] Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2003, s. 16.1

[7] Marg. Bruineman Federal bill aims to improve environmental assessments, Law Times, April 2018

Featured photo: Shutterstock

Traditional Indigenous knowledge (TK) and traditional resources have been managed by Indigenous communities since time immemorial. The arrival of...

For the last few summers news reports were dominated by coverage of raging, massive, out-of-control wildfires. The fires devastated some communities,...

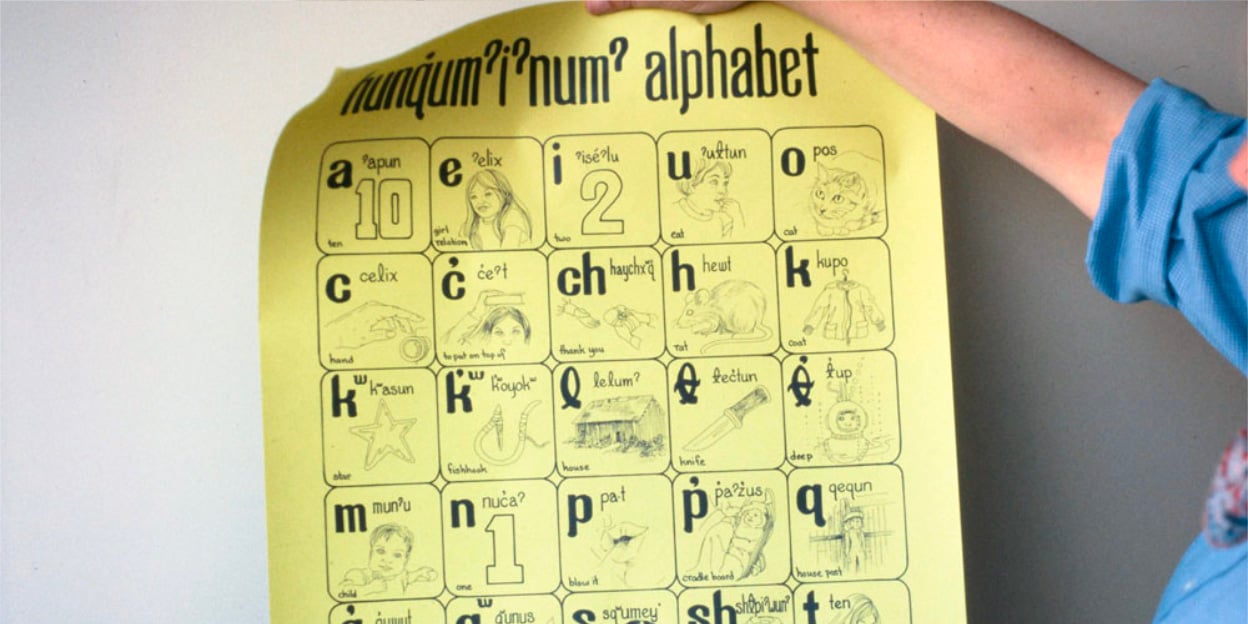

Indigenous languages the world over are in jeopardy. So much so that the United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages...