Pretendians and the Indian Act

When we prepare an article for our blog, Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples®, we put considerable thought into the title - how will it...

5 min read

Bob Joseph January 31, 2023

Education is considered a human right in Canada. Yet, while Canada has one of the world's highest levels of educational attainment, the graduation rate for Indigenous students remains far lower than that of non-Indigenous students. How is that possible? The answer lies in the history of Canada.

When the British North America Act, now known as the Constitution Act, 1867 was issued, it gave exclusive jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” to the federal government. Around the same time, the federal government signed Treaties 1 through 11, thereby assuming responsibility for the education of Indians in those treaty lands.

Eight years after the Constitution Act was issued, regulations impacting Indians were consolidated into the Indian Act, 1876. Here’s an insightful quote on how the federal government perceived its responsibility:

Our Indian legislation generally rests on the principle that the aborigines are to be kept in a condition of tutelage and treated as wards or children of the State . . . clearly our wisdom and our duty, through education and every other means, to prepare him for a higher civilization by encouraging him to assume the privileges and responsibility of full citizenship. [1]

In 1886, the federal government introduced the residential school system. Over its history (the last one closed in 1997) 150,000 children were removed from their families and communities.

When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with its parents, who are savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly impressed upon myself, as head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.

Sir John A. Macdonald, 1879

The schools aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream society through education and religious teachings. The children were taught to kneel and pray in the school's religious denomination. They were taught that their former lives were invalid (not Christian) and that their spirituality and beliefs were pagan and primitive. However, beyond that, they received little formal education. The children spent fewer hours in the classroom than they did learning trades and domestic chores. They were taught to cook, clean and work in the fields to produce food and, sometimes, revenue for the schools.

Those who survived (over 4,000 deaths documented) the physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse returned to their communities traumatized, and the connection with their family, community, language, spirituality and culture broken. They did not fit in at home or in mainstream society.

The lack of role models and mentors, insufficient funds for the schools, inadequate teachers, and unsuitable curricula taught in a foreign language all contributed to dismal success rates. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has heard many examples of students who attended residential school for eight or more years but left with nothing more than Grade Three achievement and sometimes without even the ability to read. According to Indian Affairs annual reports, in the 1950s, only half of each year’s enrolment made it to Grade Six. [2]

Here are some friction points contributing to Indigenous students' lower educational attainment rates. There is a direct link to residential schools and the Indian Act behind each one.

On-reserve schools are funded by the federal government, while the provincial governments fund other schools. Underfunding of on-reserve schools is historical and ongoing.

In 1996, the federal government capped the national funding formula at 2% per year for all First Nation programs and services. The cap remained in place until 2015, despite the rapid growth of the Indigenous population. In 2016, it was estimated that schools on reserves receive at least 30% less funding than other schools. In 2015, the 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission included the following:

8. We call upon the federal government to eliminate the discrepancy in federal education funding for First Nations children being educated on reserves and those First Nations children being educated off reserves.

9. We call upon the federal government to prepare and publish annual reports comparing funding for the education of First Nations children on and off reserves, as well as the educational and income attainments of Aboriginal peoples in Canada compared with non-Aboriginal people.

In the spring of 2018, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada published a report on the Socio-economic Gaps on First Nations Reserves—Indigenous Services Canada. The report was quite damning:

Collecting, using, and sharing First Nations’ education data

Overall message

5.38 Overall, we found that education results for First Nations students have not improved relative to those of other Canadians. We found that despite commitments the Department made 18 years ago, Indigenous Services Canada did not collect relevant data or adequately use data to improve education programs and inform funding decisions. It also did not assess the relevant data it collected for accuracy and completeness. Nor did the Department provide access to or regularly share its education information or the results of data analysis with First Nations. In addition, the Department was still unable to report how federal funding for on-reserve education compared with the funding levels for other education

systems across Canada.

5.39 These findings matter because the Department and First Nations communities that deliver education need complete and accurate data to make evidence-based decisions and, ultimately, to improve education results and socio-economic well-being. [3]

The funding allowances changed in 2019, and Indigenous Services Canada now provides guaranteed base funding per student, similar to the base funding provinces pay. An additional $1500 per student funds language and culture education. Schools on reserve will also receive additional funding based on remoteness, language, poverty rates, and school size. [4]

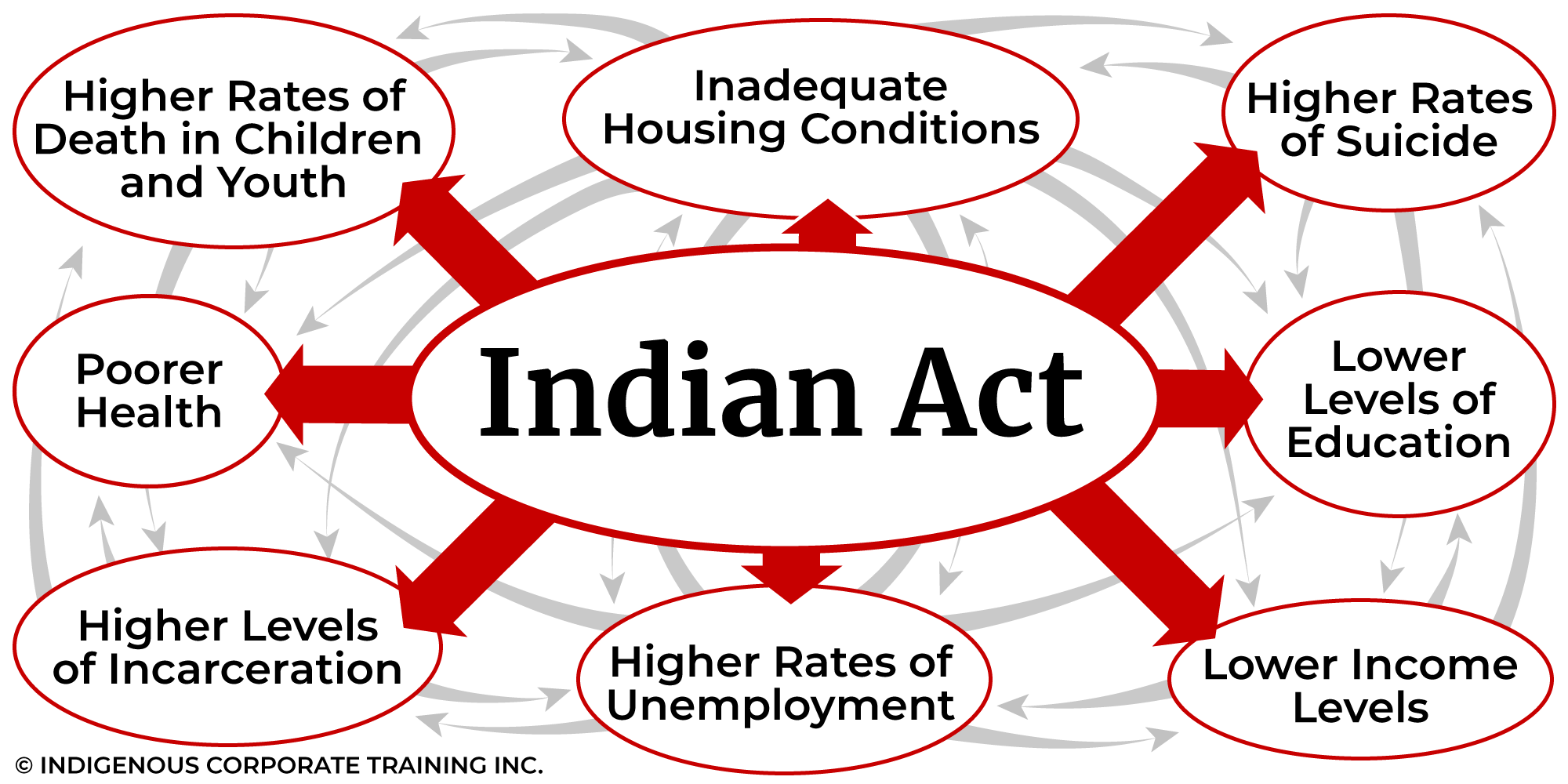

Over 150 years of inferior education have had a noticeable and devastating impact on the socioeconomic outcomes of Indigenous people. Poor education leads to chronic unemployment, which can lead to poverty, poor housing, substance abuse, family violence and ill health.

[The National Indigenous Economic Development Strategy 2022 estimates that] if access to education and training for Indigenous Peoples became equitable to non-Indigenous Peoples, the result would be an additional $8.5 billion in income earned annually by the Indigenous population. Further, the report states that closing the productivity gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians would lead to an increase of $27.7 billion to Canada's gross domestic product (GDP) each year. [5]

Education Jurisdiction Agreements are education agreements between the Government of Canada and Nations seeking to control the education of the Nation's children. Agreements can include governance processes, education standards, graduation requirements, certification of teachers and schools, and consultation and decision-making requirements.

Nations that successfully negotiate Education Jurisdiction Agreements step away from Sections 114 to 122 of the federal Indian Act. Taking control of education is essential on the long journey back to self-governance.

Consistent, equitable funding for the education of all Indigenous students is in the best interests of all Canadians.

There are many organizations (the resource sector as example) starting Indigenous employment initiatives. Our Indigenous Employment: Recruitment & Retention training is a valuable resource for those wanting to better understand the differences in employing Indigenous vs. non-Indigenous employees. You will also learn how to attract and retain Indigenous employees.

[1] Canada, Department of the Interior, Annual Report for the Year Ended 30th June 1876, Sessional Papers, 1877, vol. 7, no.II, Xiv

[2] The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Volume 5. P

[3] Office of the Auditor General of Canada, REPORT 5 Socio-economic Gaps on First Nations Reserves—Indigenous Services Canada

[4] Indigenous Services Canada (2019a)

[5] National Indigenous Economic Development Strategy 2022

Featured photo: Unsplash

When we prepare an article for our blog, Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples®, we put considerable thought into the title - how will it...

Fifty-eight percent of young adults living on reserve in Canada have not completed high school, according to the 2011 National Household Survey...

1 min read

Eight of the key issues of most significant concern for Indigenous Peoples in Canada are complex and inexorably intertwined - so much so that...