Why Is It Important to Protect & Revitalize Indigenous Languages?

Of the most spoken languages in the world, English is third after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. But English is the most commonly spoken second...

Indigenous languages the world over are in jeopardy. So much so that the United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages to raise awareness of the fragility of thousands of Indigenous languages and to underline the enormity of the situation.

Three out of four of the 60 (some sources say 90) Indigenous languages still in existence in Canada are endangered [1] as the few fluent speakers of each language age and pass on. But the reason there are so few speakers is much more complex than demographics.

The roots extend all the way back to 1876 with the passing of the Indian Act. Indigenous languages were a target of the assimilation policies of the federal government. Indigenous children (150,000 of which an estimated 6,000 did not survive) were removed from their families and communities and placed in residential schools where they were forbidden to speak their home language. When the children returned to their communities, they were often too traumatized to use their home language, lost their fluency, and did not raise their children to speak the language.

An additional impact on language continuity is the increasing trend of young Indigenous people leaving their home communities for education and employment opportunities in urban centres.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action include #13 for the federal government to acknowledge that Indigenous (Aboriginal) rights include language rights:

We call upon the federal government to acknowledge that Aboriginal rights include Aboriginal language rights.

The federal government has tabled Bill C-91, the Indigenous Languages Act, but there are concerns the Act does not provide the means of achieving those rights.

Beyond our borders, the preservation of language for Indigenous Peoples is a right under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDec). Canada is a signatory to UNDec therefore there is a responsibility to honour the commitment.

Article 13

- Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names for communities, places and persons.

- States shall take effective measures to ensure that this right is protected and also to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and be understood in political, legal and administrative proceedings, where necessary through the provision of interpretation or by other appropriate means.

Article 14

- Indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems and institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning.

- States shall, in conjunction with indigenous peoples, take effective measures, in order for indigenous individuals, particularly children, including those living outside their communities, to have access, when possible, to an education in their own culture and provided in their own language.

The discussion of the rights of Indigenous children to receive education in their language often garners the comment “how is that possible when there are 60 languages?” It has been done elsewhere and in countries with far more than 60 languages. In Papua New Guinea more than 400 local languages have been used for initial mother tongue instruction. In that country, cultural and linguistic diversity is desired and considered a source of strength.

Indigenous language classes are becoming more frequent but studying a language in a classroom isolates the language. Real proficiency in a language comes from immersion beginning at an early age.

While the destructive role of residential schools is now recognized, the modern equivalent is often overlooked: English and French remain the primary medium of instruction of Indigenous students in most schools across the country and attendance is compulsory. Even in schools with Indigenous language programs, students still do most of their learning, speaking, thinking, and functioning in English or French rather than in their ancestral language. As with residential schools, it is the absence of sustained contact with proficient adult speakers that denies children the opportunity to become fluent in their own ancestral languages. [2]

There are some very successful Indigenous language immersion programs in Canada. The Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey in Nova Scotia is a prime example:

Mi'kmaq language and immersion efforts have seen the creation of a 6,000+ word Mi'kmaq-Mi'gmag online talking dictionary. With help from the First Nation Help Desk, Mi'kmaq language classes are now offered to daycares via videoconference, and a Mi'kmaq 110/Mi'kmaw Language 11 web-based courses is offered in all high schools. St. Francis Xavier University has also delivered its first program in the Mi'kmaw language and has graduated Mi'kmaq Immersion teachers with a certificate in teaching immersion. [3]

If there were employment opportunities (government services, health care, education, retail, consultation) that required Indigenous languages that would be an additional motivator for all levels of government, education districts, and Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians to show their support for language immersion for Indigenous children.

An Indigenous language holds the history and traditional knowledge of that culture. For that reason alone, it is critical that everything possible is done to halt the rapid loss of Indigenous languages.

The movie Edge of the Knife is the first feature film to be made entirely in the Haida language.

[1] Indigenous Languages in Canada, Canadian Heritage pdf

[2] Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, and Robert Dunbar, 2010. “Indigenous Children’s Education as Linguistic Genocide and a Crime against Humanity? A Global View.” Galdu Cala: Journal of Indigenous Peoples Rights

[3] Introducing Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey

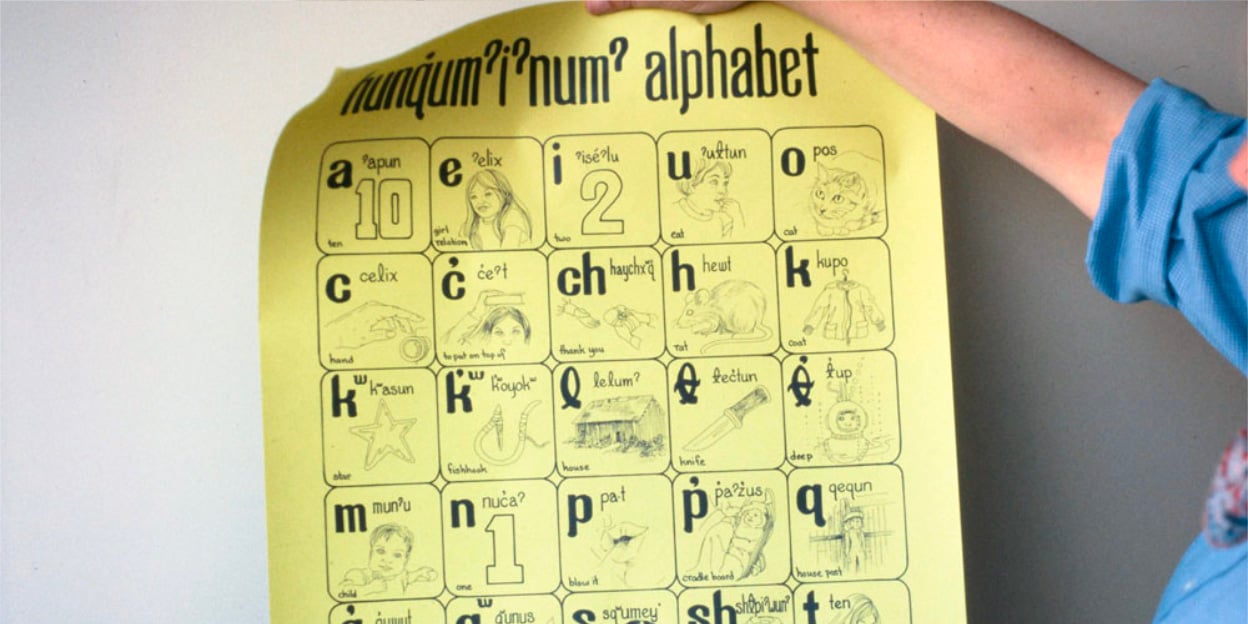

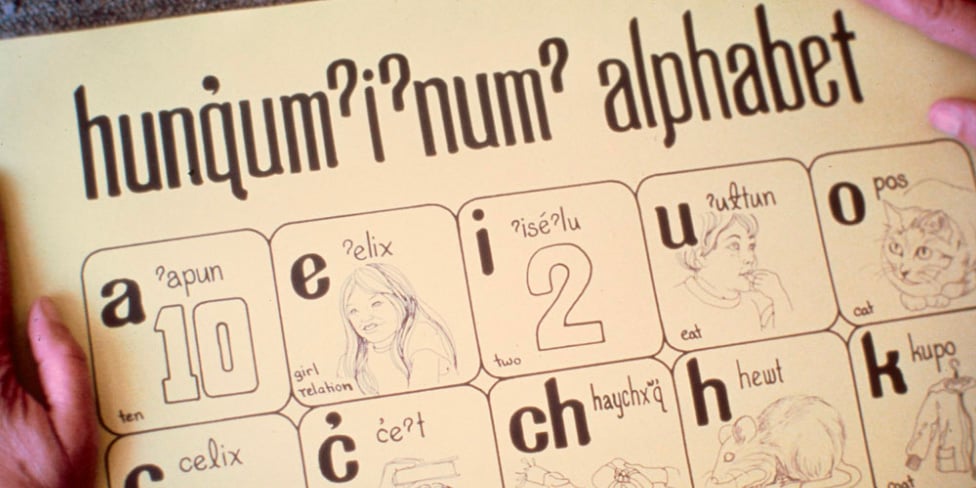

Featured photo: Hun¿qum¿i¿num¿ alphabet poster, a dialect of Halkomelem, Coast Salish. Photo: George Mully / George Mully fonds / Library and Archives Canada.

Of the most spoken languages in the world, English is third after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. But English is the most commonly spoken second...

Indigenous languages are struggling to survive. With the number of Indigenous language speakers on the decline, some of these languages are on the...

The COVID-19 pandemic could be the single greatest threat in this generation to the continuity of Indigenous cultures and the preservation of...