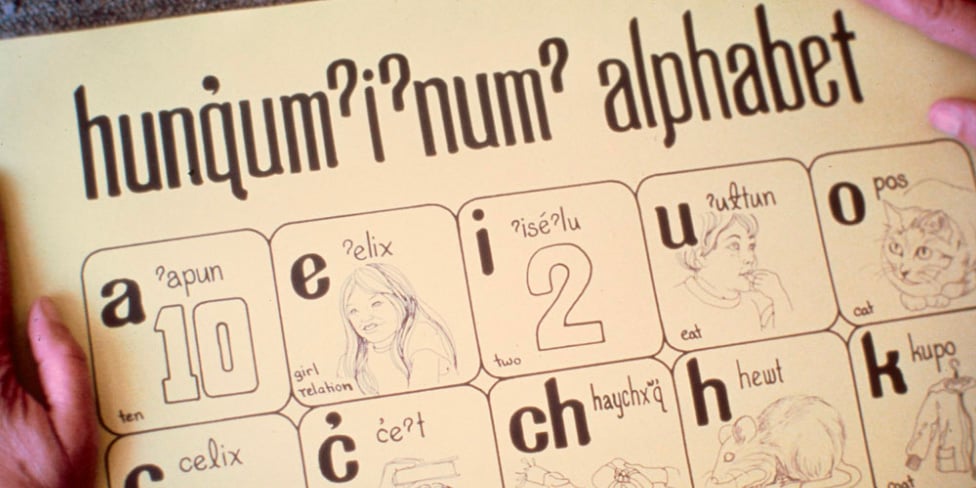

Indigenous Knowledge and the Question of Copyright

Indigenous Peoples around the world are increasingly concerned about protecting their Indigenous knowledge (IK) and traditional cultural expressions...

tsuu aay ‘kiing jah

Looking into the heart of the cedar

For thousands of years, the people went into the forest for cedar.

Among the living trees, we find some with strips of bark removed to make

clothes, hats and baskets.

We find cedar with planks split off-planks for a baby’s cradle, a cooking box,

a drum, a house and a coffin.

In the remaining forests, we find stumps marking the remains of trees crafted into

canoes, houses and to display the crests.

Some tluu will be shaped in various stages of construction.

We will look into the heart of cedar and walk in the majesty of

the great magician.

Guujaaw [1]

Culturally modified trees (CMTs) are living trees that have been visibly altered or modified by Indigenous Peoples for usage in their cultural traditions. Wherever there are or has been forest-dwelling Indigenous Peoples - North America, Australia, Scandinavia - there will be, or has been CMTs. Not all jurisdictions have protective measures in place for the preservation of CMTs and their immediate environment. In BC, groups of CMTs are classified as “forest utilization sites”. If one or more CMT in a forest utilization site can be determined as modified before 1846, then the trees in that group are protected by the Heritage Conservation Act (1966).

“Modified” means just that - the trees are altered through sustainable harvesting techniques that have been practiced and passed down through generations since time immemorial. Along the Pacific north coast, the trees most commonly modified are the red and yellow western cedar. Other species of trees were modified in other regions but in this article, we focus on the red cedar and its significance to northwest coast Indigenous cultures. The red cedar was a vital component to the lives and cultures of northwest coastal Indigenous Peoples, so vital that in some cultures the trees have their own creation stories.

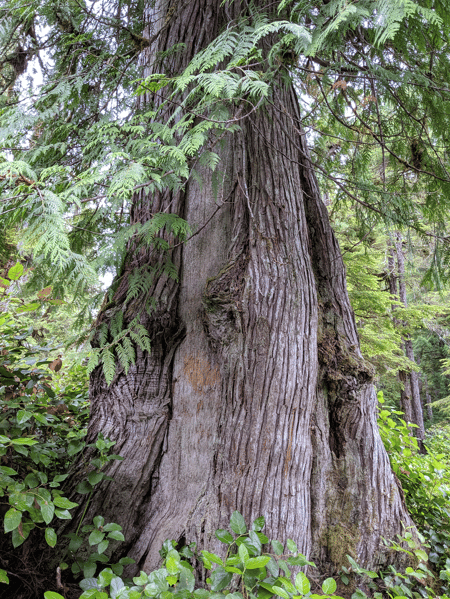

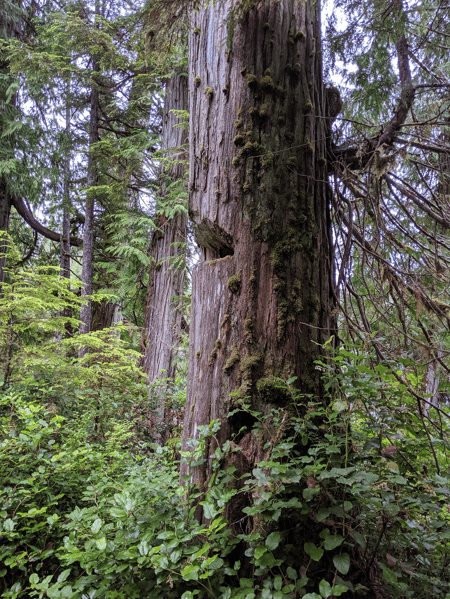

CMTs are recognizable by the scars remaining from the removal of bark, planks or test holes. Generally, material harvested impacted no more than one-third of the circumference of a tree, which allowed the tree to keep growing. Some trees display a series of scars indicating material was harvested more than once, but with decades between harvests. Leaving enough of the tree intact to heal and continue to grow is a testament to the depth of knowledge about forests and ecology.

The red cedar, in particular, is revered as the “tree of life” because nearly every part is of value to coastal Indigenous cultures - wood, bark, pitch, branches, and roots. Cedar trees provided materials for shelter, clothing, bedding, food gathering and preparation, transportation, and cultural and spiritual activities. The wood, which is relatively soft, lightweight, and splits cleanly and readily along the grain, was ideal for the stone and bone cutting and carving tools used prior to European contact.

Planks and bark boards of specific sizes were harvested for shelters. In the following two photos, you can see the rectangular scar from a bark board.

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

Trees selected for canoes or poles (house frontal poles, interior house posts and beams, mortuary poles, memorial poles, and welcome poles) were felled. Trees for these purposes had to be straight, extremely tall, and sound. The wood from a mature red cedar contains an oil that is toxic to most fungi which makes it rot-resistant. But, this toxic oil is not present in cedar saplings which means some trees can mature with rot in their core. Therefore, before a tree was felled, a test hole was drilled to see if the heartwood was sound. If the wood wasn’t sound, the tree was left standing.

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii

The inner bark, which is pliable yet strong, was used for weaving mats, clothing, blankets, ceremonial regalia, hats, as well as ropes, baskets, and nets. Bark for these purposes was harvested in long, narrow, tapered strips from trees with few large branches. If the tree was on a slope, the bark was harvested from the uphill and lateral sides of the tree, rather than on the downhill side. In this photo, you get an idea of the lengths of the strips.

A more recently modified tree; Camosun College, Victoria, BC

A more recently modified tree; Camosun College, Victoria, BC

And before anything was harvested, it was protocol for a prayer of thanks to be given to the tree and the Creator.

CMTs are of immense cultural and spiritual significance to the descendants of those who came before.

For Guujaaw, a Haida carver from Massett, CMT sites are sacred memorials to “...our ancestors who worked in the forests and created the canoes and totem poles for which the Haidas are known worldwide, and they provide “...a sense of communion with the old canoe makers.” The CMTs at the S’yaal (Collison Point) site on Haida Gwaii are considered to be “...‘living archaeology’ [that] presents a unique opportunity to get close to the activities of our ancestors in a live and dynamic setting” and “to our people the spiritual effects of being in the footsteps of our ancestors is the primary significance of the site. [2]

They are also of legal significance. Because the age of a tree can be precisely recorded, CMTs are proof of traditional, long-term occupancy and use of forests, so are powerful testaments to the strength of claim when Indigenous rights are under discussion. CMTs in British Columbia have been dated as far back as 1137 AD [3], which to put in historical perspective, is the year the Second Crusade was begun by Pope Eugenius III and European nobles to recapture the city of Edessa, an important commercial and cultural centre on the edge of the desert of Syria in Upper Mesopotamia.

If you have the opportunity to walk in an ancient forest, be on the lookout for culturally modified trees.

[1] Haida Laas, Journal of the Haida Nation, 2005, p 14

[2] Sacred Cedar The Cultural and Archaeological Significance of Culturally Modified Trees A REPORT OF THE PACIFIC SALMON FORESTS PROJECT by Arnoud H. Stryd, Ph.D. Vicki Feddema, M.A.; David Suzuki Foundation 1998 p 12

[3] ibid p 14

Featured photo: Flickr, GlacierNPS

Indigenous Peoples around the world are increasingly concerned about protecting their Indigenous knowledge (IK) and traditional cultural expressions...

Of the most spoken languages in the world, English is third after Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. But English is the most commonly spoken second...

Oral traditions retain the history of Indigenous Peoples by passing cultural information from one generation to the next. For Indigenous communities...