The Indian Act & the Politics of Exclusion

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

This article is part of our series on the Indian Act and the many restrictions historically imposed on First Nations as a means of controlling them and assimilating them into European culture. Or, in the words of John A. Macdonald “to do away with the Indian problem”.

Under the Indian Act, the reserve system was created which effectively removed First Nations from their traditional territories and lifestyles in some cases and positioned the government to attempt to dispossess them of their culture and identity. Once First Nations were moved onto the reserves, into European-style houses, given European names and entered into the register, it became much easier to administer policies.

Under the Indian Act, the reserve system was created which effectively removed First Nations from their traditional territories and lifestyles in some cases and positioned the government to attempt to dispossess them of their culture and identity. Once First Nations were moved onto the reserves, into European-style houses, given European names and entered into the register, it became much easier to administer policies.

Agriculture was chosen as the path for First Nations to follow toward “civilization”. Hayter Reed, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs from 1893 – 1897 stated “agriculture was the great panacea of what was perceived to be the ills of Canada’s Indians” [1]. This is despite the fact that many reserves were located in areas that were unsuitable for agriculture. Government agencies later used the low success rate of First Nation farmers as a reason to reduce the size of reserves.

Indian agents and farm instructors worked with the First Nations to teach them how to farm although raising crops such as corn or rice was not new to some cultures. In Saskatchewan in particular, some of the First Nation farmers were very successful and grew crops and produce, as good or better, than that produced by the settlers. They formed collectives to share the costs of new equipment and labour.

At Duck Lake in 1891, six or seven Indians together purchased a self-binder with the approval of the farm instructor. The implement dealer had to acquire the consent of the agent, who was ordered by Inspector McGibbon to object to the sale. No sale or delivery took place. [2]

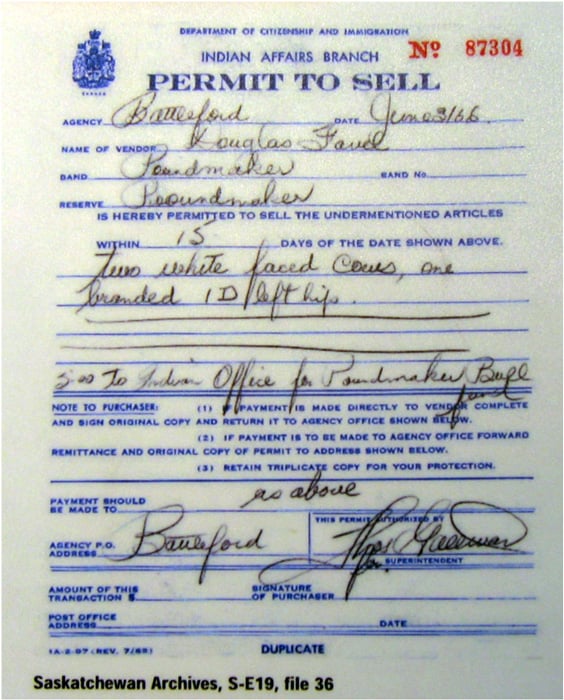

The unexpected farming success quickly became a problem and new policies were developed to protect the market share for the settlers. An Act to Amend "The Indian Act, 1880," prohibited the sale of agricultural products grown on reserves in the Territories, Manitoba or the District of Keewatin, except in accordance with government regulations. In other words, First Nation farmers had to have a permit to sell cattle, grain, a load of hay, or produce; additionally, they required a permit to buy groceries and clothes. To solidify the effectiveness of the permit system, settlers were prohibited from purchasing goods and services from First Nation farmers.

This is Section 32.1 of the Indian Act (repealed in 2014). Some Chiefs had said leave it alone and don't repeal. Their concern was that Canada would remove sections of the Act which would allow the Act to continue to exist into an undefined future. They argued that they didn't want band-aid solutions but real change away from the Indian Act and sooner than later. Real change is defined broadly in terms of Self-Determination, Self-Government, and Self-Reliance.

32. (1) A transaction of any kind whereby a band or a member thereof purports to sell, barter, exchange, give or otherwise dispose of cattle or other animals, grain or hay, whether wild or cultivated, or root crops or plants or their products from a reserve in Manitoba, Saskatchewan or Alberta, to a person other than a member of that band, is void unless the superintendent approves the transaction in writing.

Her Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada, enacts as follows:-

Governor in Council may make regulations for prohibiting or regulating sale of produce by Indians.

Publication.

- The Governor in Council may make such provisions and regulations as may, from time to time, seem advisable for prohibiting or regulating the sale, barter, exchange or gift, by any band or irregular band of Indians, or by any Indian of any band or irregular band, in the North-West Territories, the Province of Manitoba, or the District of Keewatin, any grain or root crops, or other produce grown upon any Indian Reserve in the North-West Territories, the Province of Manitoba, or the District of Keewatin ; and may further provide that such sale, barter, exchange or gift shall be absolutely null and void unless the same be made in accordance with the provisions and regulations made in that behalf. All provisions and regulations made under this Act shall be published in the Canada Gazette

Penalty for buying from Indians contrary to such regulations.- Any person who buys or otherwise acquires from any such Indian, or band, or irregular band of Indians, contrary to any provisions or regulations made by the Governor in Council under this Act, is guilty of an offence, and is punishable, upon summary conviction, by fine, not exceeding one hundred dollars, or by imprisonment for a period not exceeding three months, in any place of confinement other than a penitentiary, or by both fine and imprisonment.” [3]

The “permit system” ensured that First Nations were only able to attain a subsistence level of farming. It also limited interaction between First Nation farmers and the non-First Nations in the area.

In the 1951 Act, the “permit system” was extended to cover all First Nations but its enforcement gradually disappeared.

[1] Carter, Sarah. Lost Harvest, Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993. p 15

[2] Bateman, Rebecca. Talking with The Plow: Agricultural Policy and Indian Farming in the Canadian and U.S. Prairies. Vancouver: Simon Fraser University. p 219.

[3] An Act to amend "The Indian Act, 1880." Date: Assented to 21st March 1881

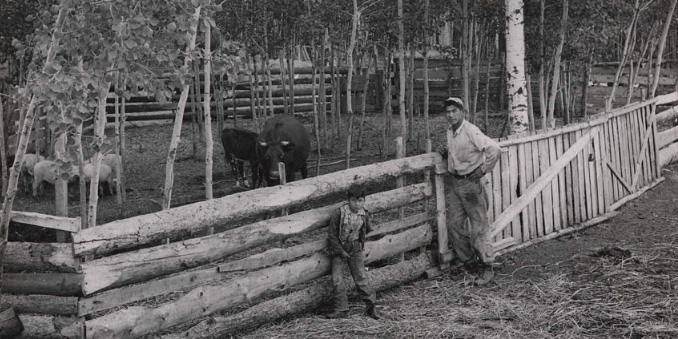

Featured photo: Photograph of Antoine Bulldog of Beaver First Nation at the Boyer River Reserve, standing beside the pasture fence with his young son. Photo: Erik Watt / Edmonton Journal / Library and Archives Canada / Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds / e011307190 ; Copyright: Edmonton Journal

Indigenous nations enjoyed full autonomy over every aspect of their lives for millennia. But, that all began to change in 1867 with the introduction...

I want to reflect on how the social and political landscape of Canada is changing. It may not be as fast as some of us would like, or as...

The incarceration rate of Indigenous peoples in Canada should be labelled a national crisis. The flaws in the justice system are insidious and...