Indigenous Peoples and COVID-19

We are in uncharted waters these days as countries around the world scramble to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. While we are all at risk and all...

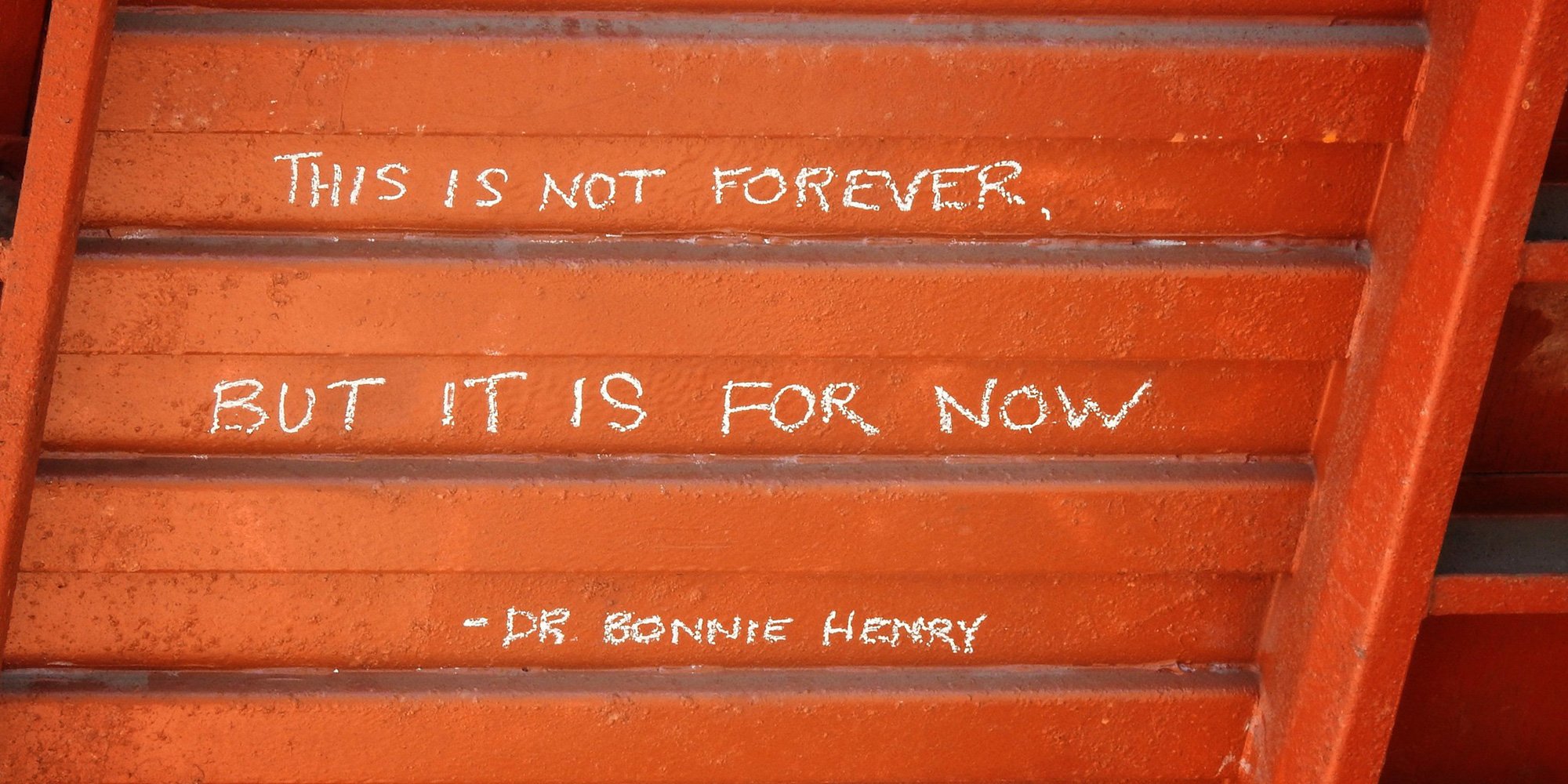

When Dr. Bonnie Henry announced the death of an Elder from Alert Bay, I was struck by her compassion, her understanding of the enormity of the immediate and long-term loss to the Elder’s family and her community, the loss to the greater society, and the deep emotion in her voice.

Included in the deaths in the last 24 hours, is our first death in one of B.C.’s First Nations communities. Along with the many lives we have lost to COVID-19, this is a tragedy that’s beyond just us. This is a tragedy for all of us. Our Elders, in particular, in our First Nations communities are culture and history keepers.

When they become ill and when they die, we all lose and I want you to know that we feel that collective loss today. My thoughts are with her family and her entire community as I recognize the tragic impact this has on all of them.

It is particularly a challenging time to not be able to come together physically, in the normal way that we would, to respect the customs that we have in communities at this time and my condolences and my heart goes out to this community and to the family.

You can listen to Dr. Henry by clicking this link; her above comments are in the first 100 seconds.

I wanted to acknowledge how much it meant to me, as an Indigenous person and as someone from Alert Bay, that the provincial health officer for B.C. would make note of the magnitude of familial and cultural loss that occurs when an Indigenous Elder passes on. To include mention of the impact brought awareness to the vast number of British Columbians who tune in for her daily report.

Our Elders are the “encyclopedias” of our culture. They hold our history, language, culture, traditional knowledge, ceremonies, protocols, worldviews, creation stories, healing practices, songs, food gathering, and cooking techniques - everything that defines a culture and defines those of that culture. Traditionally, since time immemorial, that information has been shared orally, therefore, each time we lose an Elder we lose an irreplaceable piece of our histories, our culture, and our identity, which is what Dr. Henry spoke to when she said “culture and history keepers.”

The skeptics out there might be inclined to think that the passing of knowledge orally is a flawed system because of its vulnerability. But, knowledge had been passed fluidly through the generations for thousands of years. The vulnerability only became an issue following the arrival of Europeans and the introduction of pathogens which led to a devastating loss of life in immune vulnerable Indigenous communities.

The high court recognizes and accepts the validity of oral history. It was recognized in the precedent-setting 1997 Supreme Court of Canada ruling on Delgamuukw, which acknowledged Aboriginal title could exist. During the trial, Indigenous Elders orally presented evidence of their history on their traditional lands. Chief Justice Lamer’s judgement included this passage from the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996):

84 This appeal requires us to apply not only the first principle in Van der Peet but the second principle as well, and adapt the laws of evidence so that the aboriginal perspective on their practices, customs and traditions and on their relationship with the land, are given due weight by the courts. In practical terms, this requires the courts to come to terms with the oral histories of aboriginal societies, which, for many aboriginal nations, are the only record of their past. Given that the aboriginal rights recognized and affirmed by s. 35(1) are defined by reference to pre-contact practices or, as I will develop below, in the case of title, pre-sovereignty occupation, those histories play a crucial role in the litigation of aboriginal rights. [emphasis added]

85 A useful and informative description of aboriginal oral history is provided by the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996), vol. 1 (Looking Forward, Looking Back), at p. 33:

The Aboriginal tradition in the recording of history is neither linear nor steeped in the same notions of social progress and evolution [as in the non-Aboriginal tradition]. Nor is it usually human-centred in the same way as the western scientific tradition, for it does not assume that human beings are anything more than one -- and not necessarily the most important -- element of the natural order of the universe. Moreover, the Aboriginal historical tradition is an oral one, involving legends, stories and accounts handed down through the generations in oral form. It is less focused on establishing objective truth and assumes that the teller of the story is so much a part of the event being described that it would be arrogant to presume to classify or categorize the event exactly or for all time.

In the Aboriginal tradition, the purpose of repeating oral accounts from the past is broader than the role of written history in western societies. It may be to educate the listener, to communicate aspects of culture, to socialize people into a cultural tradition, or to validate the claims of a particular family to authority and prestige… [emphasis added]

Oral accounts of the past include a good deal of subjective experience. They are not simply a detached recounting of factual events but, rather, are “facts enmeshed in the stories of a lifetime”. They are also likely to be rooted in particular locations, making reference to particular families and communities. This contributes to a sense that there are many histories, each characterized in part by how a people see themselves, how they define their identity in relation to their environment, and how they express their uniqueness as a people. [emphasis added]

The next large impact on the continuity of culture was the assimilation policies of the Indian Act, introduced in 1876 by Canada’s founding fathers. Under the Indian Act, the residential school system, which was introduced in 1886 and continued until 1996, saw 150,000 children removed (of which 6,000 died or disappeared) from their homes and cultures. While in those schools, the children were forbidden to speak their language, practice their culture or find solace in their spirituality. The impact of the schools is ongoing.

The magnitude of the loss of those who are the last remaining speakers of a language is devastating to a culture. I say this as an Indigenous person with a “conversational” level of fluency in my home language Kwak’wala. And, with a worldwide current rate of a language lost every two weeks, the importance of protecting our Elders and knowledge keepers is paramount.

I’ve noticed that the term Elder is being used to include all persons of advanced age. A question we are often asked in our Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® training is “Do advanced years automatically earn you the title of Elder?” Generally speaking, in Indigenous cultures, it may be incorrect to assume that the title “Elder,” as in a knowledge keeper, refers to all persons of advanced years. I learned firsthand while visiting a community that some cultures groom young people who exhibit certain characteristics to grow into the role of Elder as a knowledge keeper.

And, on another part of the spectrum, there is a lifestyle component to who is and is not considered an Elder. Not all persons of advanced years have respected their culture or devoted themselves to accruing the knowledge of their Elders. In other words, advanced years do not automatically earn the title of Elder as a knowledge keeper.

I really want to thank Dr. Bonnie Henry for her inclusive words, her compassion, and her wisdom as she leads us through this pandemic. When we tune in for our daily update on statistics and projections I am immensely grateful to her for guidance on continued physical distancing, her understanding of the toll on families and businesses, and for her calm encouragement that if we all follow the guidelines we will all be contributing to flattening the curve and preventing it from spiking if and when the province opens up.

Check out Dr. Bonnie Henry’s book: Soap and Water & Common Sense

Featured photo: Dennis Sylvester Hurd, Flickr

We are in uncharted waters these days as countries around the world scramble to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. While we are all at risk and all...

In August 2018, the federal government announced it would declare a federal statutory holiday to mark the legacy of the residential school system....

The COVID-19 pandemic could be the single greatest threat in this generation to the continuity of Indigenous cultures and the preservation of...