The Indian Act Naming Policies

The federal government’s Indian Act policies for Indians or First Nation(s) people during the nineteenth century were primarily concerned with...

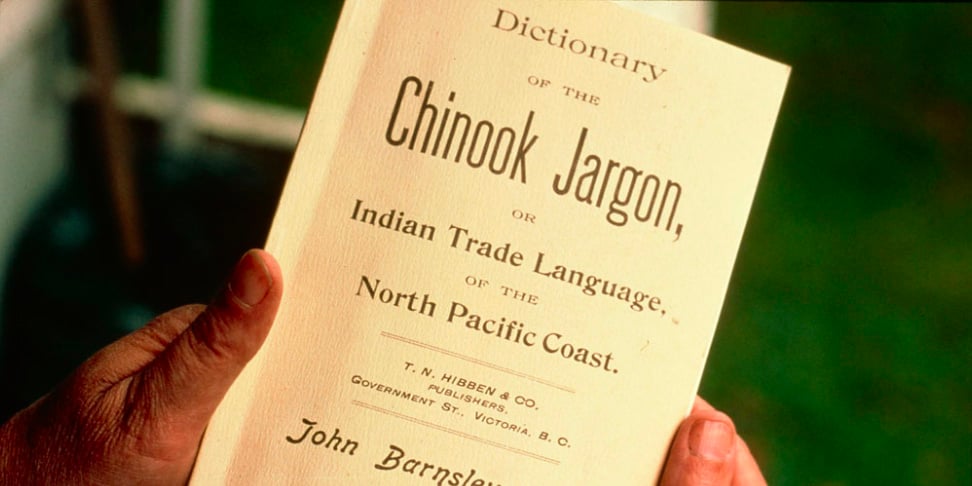

It’s quite likely that at least one of the above words is familiar, especially to those who live in the Pacific Northwest. What do these words all have in common? They are from the Chinook Jargon, also known as chinuk wawa. At the end of this article, we have a few more, with definitions.

Chinook Jargon allowed travellers and traders from very diverse cultures with completely different languages the ability to communicate with each other thereby promoting the exchange of goods, services, and ideas over vast areas of country.

Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples®, 4th edition

There is a commonly held belief that Indigenous Peoples were living in isolated communities, limited by topography. This isolation was thought to prohibit them from moving large numbers of goods, services, or ideas. In fact, prior to contact by European explorers, Indigenous Peoples had extensive trade networks in place allowing for the movement of people and goods over hundreds of miles at a time. To learn more about pre-contact Indigenous history and practices, we recommend signing up for our Working Effectively With Indigenous Peoples® training.

On the west coast of North America, these trade networks extended from Alaska to California, and even into other provinces and states. These networks were made possible by water-way travel across the ocean, rivers and lakes, and by the existence of a common language, Chinook Jargon. As the Pacific Northwest was one of the most linguistically diverse regions in North America, it was critical to have a common language of trade.

The language really exploded, but in an altered state, with the arrival of Europeans and their need to trade, and the need for First Nations and Native Americans to have words to identify unfamiliar objects. The original Chinook Jargon had a number of sounds that were difficult for Europeans to pronounce so early settlers and traders adapted the more commonly used words into ones they could pronounce. Thus, a simplified version of the language was created and by the end of the 1900s, this simplified version of the Jargon was extensively used throughout the Pacific Northwest.

By the late 1800s, the Jargon had become the working person’s language. Indigenous people were increasingly employed in canneries, fishing, logging and ranching. Non-Indigenous working in these industries became fluent, as did the merchants who provided goods and services to the industries.

It also found a home in the churches as missionaries, in their desire to convert Indigenous people, translated hymns and prayers into the Jargon. This increased influence of the oral Jargon led inevitably to the need for a written version. In 1891, Father Jean-Marie-Raphaël Le Jeune published a newspaper, the Kamloops Wawa or “Talk of Kamloops”, written in Chinook Jargon, as well as in French, English and other local traditional languages; the newspaper continued for about a decade. Father Le Jeune adapted the French Duployan shorthand script for the Chinook Jargon articles; the adapted script was known as “wawa”. Father Le Jeune fortuitously met Charlie Alexis Mayous, a First Nation man to whom he taught the shorthand. Mayous very quickly memorized all the prayers in Chinook, French and English so was able to teach other First Nations to speak and write the Chinook Jargon.

The usage of the language of trade ironically declined with improved and expanded methods of shipping goods. The advent of the railroad dramatically changed the way goods and people moved. The railway brought more English-speaking settlers to the Northwest which resulted in Aboriginal people having to learn English to survive rather than the other way round. The assimilation policy further shut down usage of the language, and those who continued to use it were shunned.

There is a strong interest in reviving the Jargon as it was an important language pre-contact and played a “skookum” role in the development of the Pacific Northwest.

Iona Campagnolo, at her swearing-in in 2001 as Lieutenant Governor, famously concluded her speech, in Chinook with this: "konoway tillicums klatawa kunamokst klaska mamook okoke huloima chee illahie" which translates as "everyone was thrown together to make this strange new country (British Columbia)" - which is a very good description of BC’s history.

A few words from the Chinook Jargon that you might use yourself or see used as place names:

chuck - water;

iktus - stuff;

masi - thank you (adaptation from merci);

muckamuck, high muckamuck - literally means “big feed” but is commonly used to refer to the main person, leader, or boss sitting at the head of the table;

patlatch (potlatch) - give;

skookum - big, strong, reliable;

tillicum - friend; people;

tyee - leader, chief, boss.

Did you know? In BC there are seven major language families broken up into over 30 different dialects.

Featured photo: Dictionary of Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa), Coqualeetza Library. Photo: George Mully / George Mully fonds / Library and Archives Canada

The federal government’s Indian Act policies for Indians or First Nation(s) people during the nineteenth century were primarily concerned with...

June is National Indigenous History Month - a time for all Canadians - Indigenous, non-Indigenous and newcomers - to reflect upon and learn the...

The United Nations has declared 2022-2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages. Many Indigenous languages across the world are in...