1 min read

Was There an Upside to Residential Schools? Answer: No

"I speak partly for the record, but mostly in memory of the kindly and well-intentioned men and women and their descendants — perhaps some of us...

This article includes a video of a conversation I had with my father Chief Robert Joseph, O.C., O.B.C., about his first day at residential school and how he felt when he took his children to school.

NOTE: This article was originally published in 2020 and updated in October 2024. COVID-19 restrictions (including social distancing and mask-wearing in public places/schools) have now been lifted.

The return to school in September fills some with great glee and others with a pit of dread in their stomach. This year, under the shadow of COVID-19, teachers, parents, and caregivers, alike share a common theme of deep concern and anxiety about how safety measures of physical distancing can be managed in classrooms, during recess and lunch breaks, and during sports activities in order to protect the students.

News feeds are full of education ministers, school boards, teachers and parents voicing their opinions and concerns. The fear of the unknown is present in every family, no matter their socio-economic status, geographic location or racial identity. The fear touches everyone, whether you’re a parent, caregiver, or educator. There has never been such intense angst about children going to school. Or has there been?

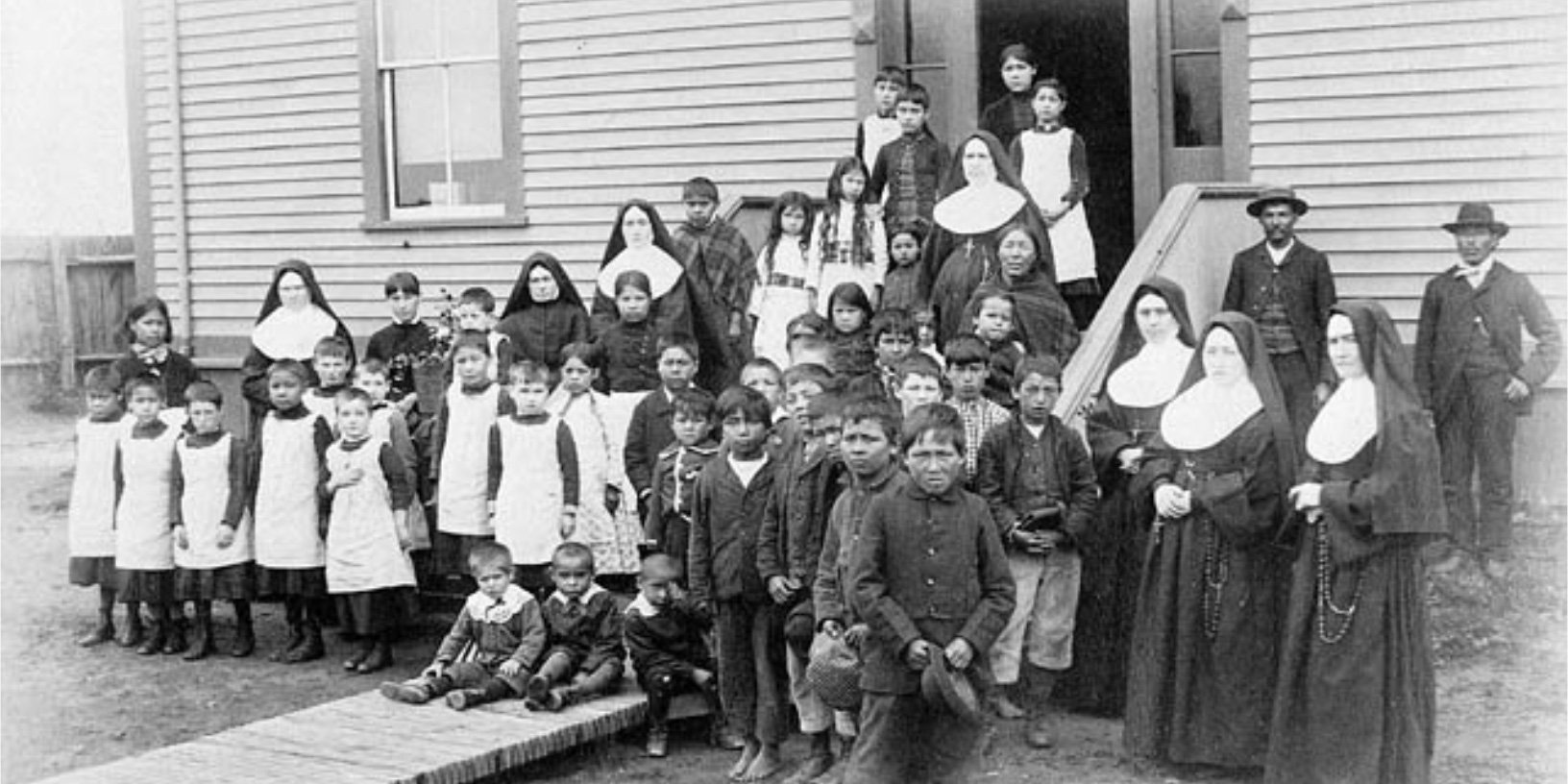

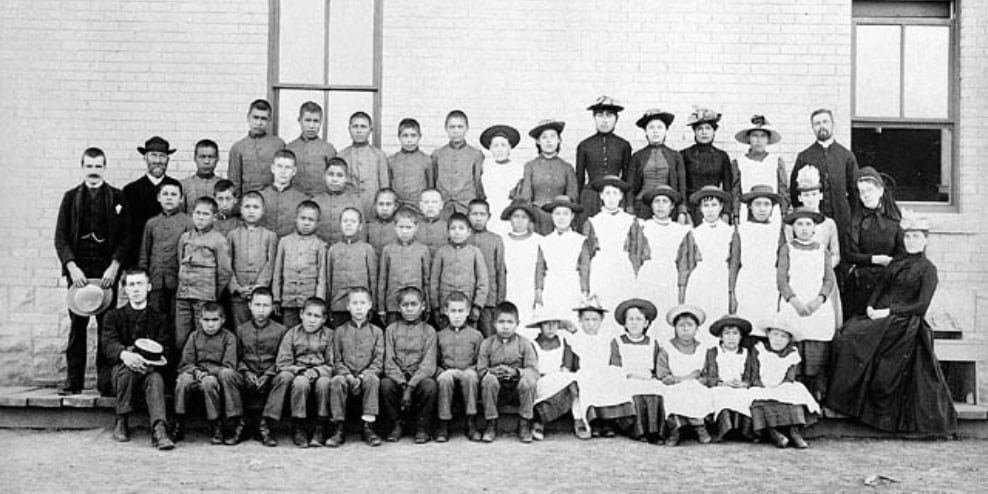

From 1886 until 1997, 150,000 children attended residential schools across the county. While the majority of the parents of those children did not voluntarily send their children to school, some students were voluntarily enrolled by their parents because they naively believed it was best for their children as they would receive an education. However, if they changed their minds, and tried to later remove their child they found they were unable to do so. The Indian Affairs department had given itself a provision that with enrollment came guardianship - parents found out after the fact that by voluntarily enrolling their children in a school they were, in fact, signing over guardianship to the federal government and it was the federal government that oversaw all discharges.

Typically, in late September, when community members had returned from traditional harvesting activities, buses and trucks would arrive to collect the children. Children were literally peeled from the arms of their parents or grandparents. English was not commonly spoken in many Indigenous communities so there was a severe communication barrier. Parents and grandparents were unable to question those who were taking the children (generally it was the NW RCMP, federal Indian Agents, and local constabulary). All they knew was that their children were being taken and that they had no recourse to prevent it. Some hid their children in the bush rather than let them be taken. By 1927, under the Indian Act, it was a punishable offence to keep your child home.

In order to educate the children properly, we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that this is hard but if we want to civilize them we must do that.

Hector Langevin, Public Works Minister of Canada, 1883 [1]

The children who attended the schools suffered horrific physical, emotional, sexual, and spiritual abuse and malnutrition. They received little in the way of reading and writing instruction. They were put to work in the kitchen, the laundry, and farmyards. They were unpaid, underfed labour. Of the 150,000 known to attend, it is estimated that 6,000 children died or disappeared. Why is it an “estimated” number? Because accurate records of the deaths and disappearances were not kept.

In this video, I ask my father Chief Dr. Robert Joseph, two questions:

As successive generations of children passed through those schools and became parents themselves, imagine how they felt when the buses and trucks came for their children, knowing what lay ahead.

How was it that residential schools operated for so long without any public outcry? Why was there no media attention? Why did the papers not carry the stories? Because the residential schools were for the most part, unseen and unknown. And that’s the way the government wanted it.

A turning point in the collective consciousness came in 2008 when Prime Minister Harper delivered a formal apology in Parliament for the residential schools. The treatment of children in residential schools was described as a “sad chapter in our history” in the opening of the Statement of Apology.

But It was not until 2015 when the Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) published its report that the extent of the depravity of the schools and the duplicity of the government in covering it up fully dawned on Canadians. The report sent shock waves of shame, anger and disbelief through Canadians when they learned of the horrors thousands of children over seven generations endured unbeknownst to them.

We encourage those that would like to take a deeper look at the many impacts of residential schools on the Indigenous population in Canada, to enrol in our Working Effectively With Indigenous Peoples® training.

It is so much more than a “sad chapter in our history.” What was termed a “sad chapter” has been classified as cultural genocide. Yet, this “sad chapter” was not included in our education system until after the TRC’s calls to action in 2015.

Here is an interesting insight into the age of awareness about residential schools based on an August 2020 online survey:

While only 26 per cent of respondents aged 18 to 34 say they did not discuss this topic inside the classroom, the proportion jumps to 51 per cent among those aged 35 to 54 and 58 per cent among those aged 55 and over. [2]

Sending our children to school with the looming threat of COVID-19 when there are so many variables and unknowns is not an easy decision but parents and caregivers have options. Be thankful you have the freedom and ability to communicate with your school district and teachers. I wish everyone a safe return to school.

[1] "They Came for the Children: Canada, Aboriginal Peoples, and Residential Schools" Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, (Manitoba: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Report, 2012): 5

[2] Nearly half of Canadians never learned about residential schools as students: survey

Featured photo: H.J. Woodside / Library and Archives Canada / PA-123707

1 min read

"I speak partly for the record, but mostly in memory of the kindly and well-intentioned men and women and their descendants — perhaps some of us...

There has been some discussion in the media recently about those who attended residential school having post-traumatic stress disorder, sometimes...

In 1844, the Bagot Commission of the United Province of Canada recommended training students in “…as many manual labour or Industrial schools as...