Indigenous Veterans: Equals on the Battlefields, but Not at Home

Indigenous Peoples in Canada have fought on the front line of every major battle Canada has been involved in, and have done so with valour and...

5 min read

Bob Joseph November 06, 2025

November 8 is National Indigenous Veterans Day, a memorial day observed to honour the contributions and sacrifices of Indigenous Peoples who served in the Canadian Armed Forces.

If you are unfamiliar with the significant contributions of Indigenous veterans during World War I and II, and the Korean War, here are some facts to pique your interest and build your knowledge.

“Voluntary enlistment was high…..In Aboriginal communities where health and education levels were advanced, virtually every eligible man joined the armed forces. The overwhelming support for Canada's war effort — shown through enlistment, contributions to war charities and labour in wartime industries — was a measure of Aboriginal people's willingness to assume their responsibility in the crisis facing Canada. ” [1]

There were many driving forces for voluntary enlistment. In WWI, Indigenous Peoples were initially dissuaded from joining the military, but as casualties rose overseas and the demand for volunteers increased, they were encouraged to enlist.

In particular, many Indigenous men answered King George V’s call for “able-bodied men” to join the war effort. This was not out of national pride or support for the Canadian government, but in order to honour their duty to protect the Crown. [2]

Starting in World War II, both Indigenous men and women could enlist. Many Indigenous Peoples enlisted in the Canadian military as a way to escape from residential schools and poverty.Due to the poverty, and diseases on reserves, hundreds and perhaps thousands of Indigenous people were unable to pass medical examinations, “no figures cited to gauge their participation in the war are ever likely to reflect with any accuracy their widespread willingness to serve.” [3]

In the First World War, “The casualties of war included many of the officers and decorated soldiers. In all, more than 300 status Indians died… Hundreds of others were wounded, many of whom died soon after the war. In addition, disease took a heavy toll; the isolation of many reserves and Aboriginal communities meant that immunity to some diseases was low.” [4]

At the end of the Second World War, Indian Affairs reported that 3,090 status Indians had participated in the war “(2.4% of the 125,946 status Indians identified in the Canadian census).” [5] Again, this figure does not include non-status Indians, Inuit and Métis soldiers.

It is estimated that “12,000 Aboriginal people served in the two world wars and Korea, an estimate that certainly appears reasonable.” [6]

It is difficult to determine the precise number of Indigenous veterans who served, and this figure of 12,000 is a safe average.Despite the many decades of poverty brought about by life on a reserve and restrictive government policies and the additional hardships induced by the absence of most able-bodied men who had left to join the armies, Indigenous communities felt compelled to contribute to various war funds. Approximately $44,000 was raised and donated during the First World War and during the Second World War, they raised and donated over $23,500. The communities raised money by:

...holding dances, sales, exhibitions and rodeos; they collected scrap tires and iron. One of the most outstanding examples of Indian generosity came from Old Crow, Yukon. Old Crow Chief Moses walked from his home into Alaska, carrying the community's winter furs. After selling them, he walked back to the nearest RCMP post and handed over some $400 to be donated to the orphan children of London, England. The BBC and the government of Canada made much of this incident, sponsoring a broadcast by Indian soldiers in Britain. Before long, Old Crow had raised more money, this time for the Russian Relief Fund. Not content to rest on their laurels, the same band next contributed $330 to the relief of Chinese victims of war. [7]

Indigenous communities contributed to the war effort at home by donating money, clothing, and food. The government also expropriated reserve land. [8]

Upon returning from war, veterans would be given parcels of reserve land. However, this was an empty gesture. Indigenous veterans legally couldn’t own reserve land, and often weren’t welcome back on reserve, particularly because the land they were given was taken from other Indigenous Peoples in their community. The land was also often left full of munitions.

Enfranchisement was extended to include status Indians who joined the military. Status Indian veterans returning from the Second World War found that while they may have fought for their country, they had lost their status in the process and had no home to return to.

The right to vote was also tied to enfranchisement until 1960 when Status Indians were deemed worthy of being able to vote in federal elections.Less than five years after the end of the Second World War, Canada would enter the Korean War on June 25, 1950, and several hundred Indigenous Canadians would participate in this conflict as well. Many of those who enlisted had taken part in the Second World War, and service in Korea would see them expanding on their previous duties. [9]

In 1993, Mayor Susan Thompson of Winnipeg was the first to recognize November 8th as Aboriginal Veterans Day, with Manitoba following as the first province to recognize it in 1994.

It was not until the 1990s, almost fifty years after the Second World War, that Indigenous Peoples were allowed to lay wreaths at the National War Memorial.

On November 11, 1991, a group of Kanien'kehaka (Mohawk) veterans tried to place a wreath during a Remembrance Day ceremony but were refused. This led to the founding of several veterans groups, and the later push to acknowledge November 8th as Aboriginal Veterans Day (see Fact #9).

1992 was the first time a recognized Indigenous veterans group, then called the National Aboriginal Veterans Association (NAVA), was allowed to lay a commemorative wreath during a Remembrance Day ceremony.

The National Aboriginal Veterans War Memorial was unveiled in Ottawa on June 21, 2001. However, the original design did not feature any women on it, and female Indigenous veterans had to fight for their inclusion on the war memorial.

On June 6, 2005, the 61st anniversary of D-Day, twenty Indigenous veterans of the Second World War were honoured at the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery in France, near Juno Beach.

At least 33 Indigenous soldiers are buried at the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. [10]

“Today, an extraordinarily diverse contingent of more than 1,200 First Nations, Inuit and Métis people serve with the Canadian Armed Forces, representing many distinct cultures and over 55 dialects.” [11]

This article was originally written in 2016 and was updated in November 2025. We would like to give special thanks to Randi Gage, who was kind enough to meet with us and share her knowledge and experiences. Ms. Gage is a veteran and advocate who was essential to the establishment of November 8th as Indigenous Veterans Day, among a long list of other accomplishments and honours.

.

[1] Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

[2] James Dempsey, quoted in The Ottawa Citizen, 05 November 2021

[3] Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

[4] Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military Chapter five: the World Wars

[5] ibid

[6] Paul Bilodeau, “Indian Veterans’ Benefits to be Surveyed”, The Edmonton Journal, 29 June 1983

[7] Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

[8] Indigenous Veterans, Government of Canada

[9] ibid

[10] Aboriginal veterans honoured in Normandy, CBC

[11] Government of Canada, Statement on Aboriginal Veterans Day

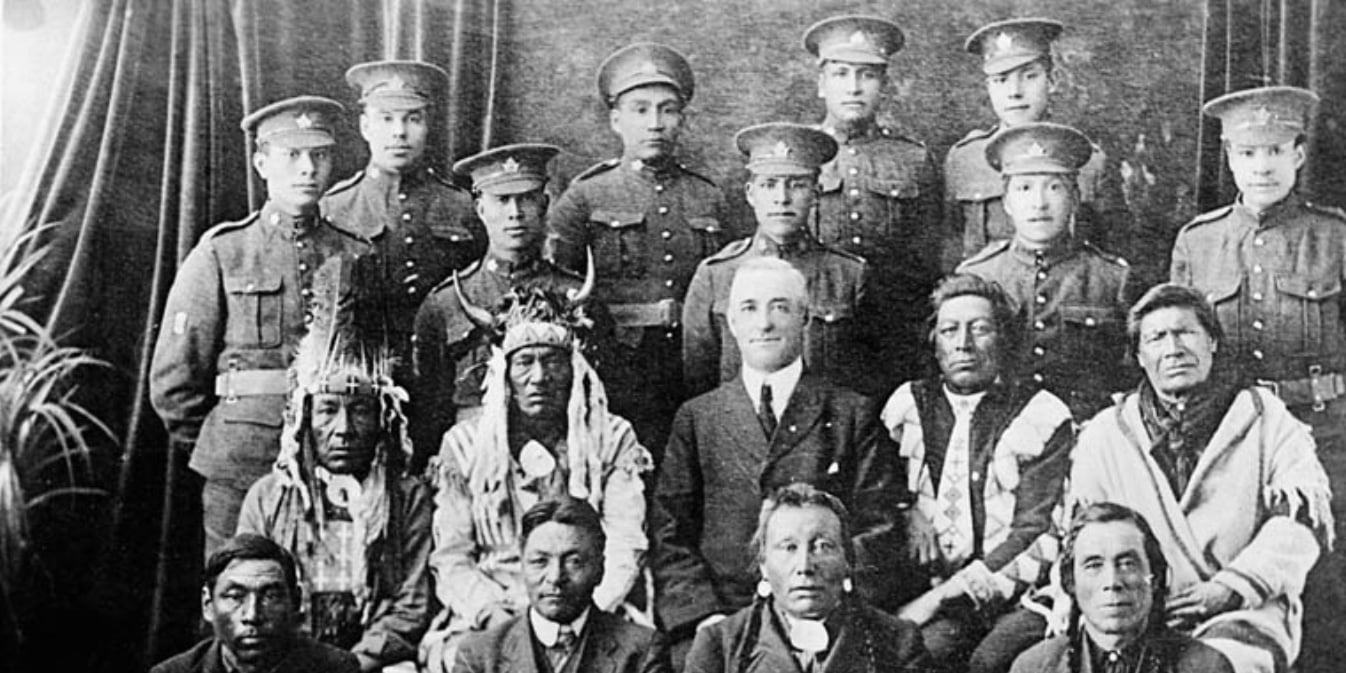

Featured photo: Private Patrick Joseph Augustine (Tjopatlig), Mi'kmaq traditional chief of the Big Cove Reserve, Big Cove, N.B., serving with the 1st Battalion, Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, with the Canadian NATO Brigade. Photo: Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds / e011308624 ; Copyright: Government of Canada

Indigenous Peoples in Canada have fought on the front line of every major battle Canada has been involved in, and have done so with valour and...

First commemorated in 1994, National Indigenous Veterans Day, November 8th, is a day to remember and recognize Indigenous contributions to military...

June is National Indigenous History Month - a time for all Canadians - Indigenous, non-Indigenous and newcomers - to reflect upon and learn the...