Lower Income - #4 of 8 Key Issues for Indigenous Peoples in Canada

Indigenous Canadians earn about 70 cents for every dollar made by non-Indigenous Canadians, according to Canada's income data. This is a very...

The first thing to know about the Indian Act electoral process is that if you are chief or council, you are elected by your people, but you are accountable to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.

Ever since the arrival of the colonizers and the imposition of their governance systems throughout Canada, the Aboriginal peoples have resisted and struggled to reconstitute their traditional forms of political representation and governance practices, to maintain control of their own affairs, and to have governments be accountable to them. [1]

As stated in the quote above, the imposition of the Indian Act electoral system undermined a tradition of self-governance that had existed effectively for thousands of years. The imposed system displaced traditional political structures and did not reflect, consider or honour First Nation needs or values. It also did not recognize that each Nation had its own style of governance with specialized skills, tools, authority and capacity developed over centuries. It was designed for assimilation – to remake traditional cultures in the image of the colonizers.

European-style elections were first introduced under An Act for the gradual enfranchisement of Indians, the better management of Indian affairs, and to extend the provisions of the Act 31st (Assented to 22nd June, 1869). The impetus behind the elective system was to replace what was viewed as an “irresponsible” system – in other words, traditional band and tribal government which were viewed as an impediment to advancement with a responsible system which was "designed to pave the way to the establishment of simple municipal institutions". [2]

This Act stipulated that elections were to be held every three years “unless deposed by the Governor for dishonesty, intemperance, or immorality” [3], only males over the age of 23 were allowed to vote, and the chiefs were granted little in the way of bylaw powers. Control of many elements of the reserve – land, resources and finance for example – passed into the hands of the Department of Indian Affairs (Crown-Indigenous Relations) as the people were considered unsophisticated and incapable of managing their own affairs. This paternalistic attitude continues today.

The responsibilities of the elected chiefs were limited to framing the rules for:

63. The chief or chiefs of any band in council may frame, subject to confirmation by the Governor in Council, rules and regulations for the following subjects, viz. :

- The care of the public health;

- The observance of order and decorum at assemblies of the Indians in general council, or on other occasions;

- The repression of intemperance and profligacy;

- The prevention of trespass by cattle;

- The maintenance of roads, bridges, ditches and fences;

- The construction and repair of school houses, council houses and other Indian public buildings;

- The establishment of pounds and the appointment of pound-keepers;

- The locating of the land in their reserves, and the establishment of a register of such locations.” [4]

In 1920, the Indian Act was amended to allow the Department of Indian Affairs to ban the hereditary rule of bands. [5] We were unable in our research to find a date for when this was repealed.

The Indian Act election system, in which the majority of our First Nation members still operate, has severely impacted the manner in which our societies traditionally governed themselves. It has displaced or attempted to displace our inherent authority as leaders and has eroded our traditions, culture and belief systems. It does not reflect our needs and aspirations. It has also not kept pace with principles of modern and accountable governments. [6]

When the three-year election cycle was reduced to a two-year election cycle it exacerbated the ability of the Chief and Council to make any significant progress on long-term development initiatives, govern and act in the best interests of their citizens, or build effective foundations for community development.

The potential for leadership changes every two years can make it difficult for economic development projects to progress, especially some of the resource development projects that are decades in the planning phase. Political instability and economic development are not good bedfellows.

The two-year cycle also makes it difficult for tribal groups to work together on larger initiatives because elections are all held at different times. Different chiefs, who may not be up to speed or may have a different vision, join the group at different times which impedes the progress of the initiative.

There have since been options developed for First Nations to move to a four-year election cycle. On April 2, 2015, the First Nations Elections Act and the First Nations Elections Regulations came into force:

Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples® tip: always do your research on the community you are planning to work with to find out if there is a hereditary chief as well as an elected chief and council.

Here’s a short video clip of comedian Rick Mercer with his take on the Indian Act.

[1] First Nations Elections: The Choice is Inherently Theirs, Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples

[2] Canada. Department of Indian Affairs. Annual Report, 1870, p. 4: Deputy Superintendent William Spragge to Secretary of State Joseph Howe, 2 February 1871.

[3] An Act for the gradual enfranchisement of Indians, the better management of Indian affairs, and to extend the provisions of the Act 31st

[4] ibid

[5] History of the Canadian Peoples, 1867–present, Alvin Finkel & Margaret Conrad, 1998

[6] First Nations Elections: The Choice is Inherently Theirs, Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, 27 October 2009, Lawrence Paul, Co-Chair, Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat.

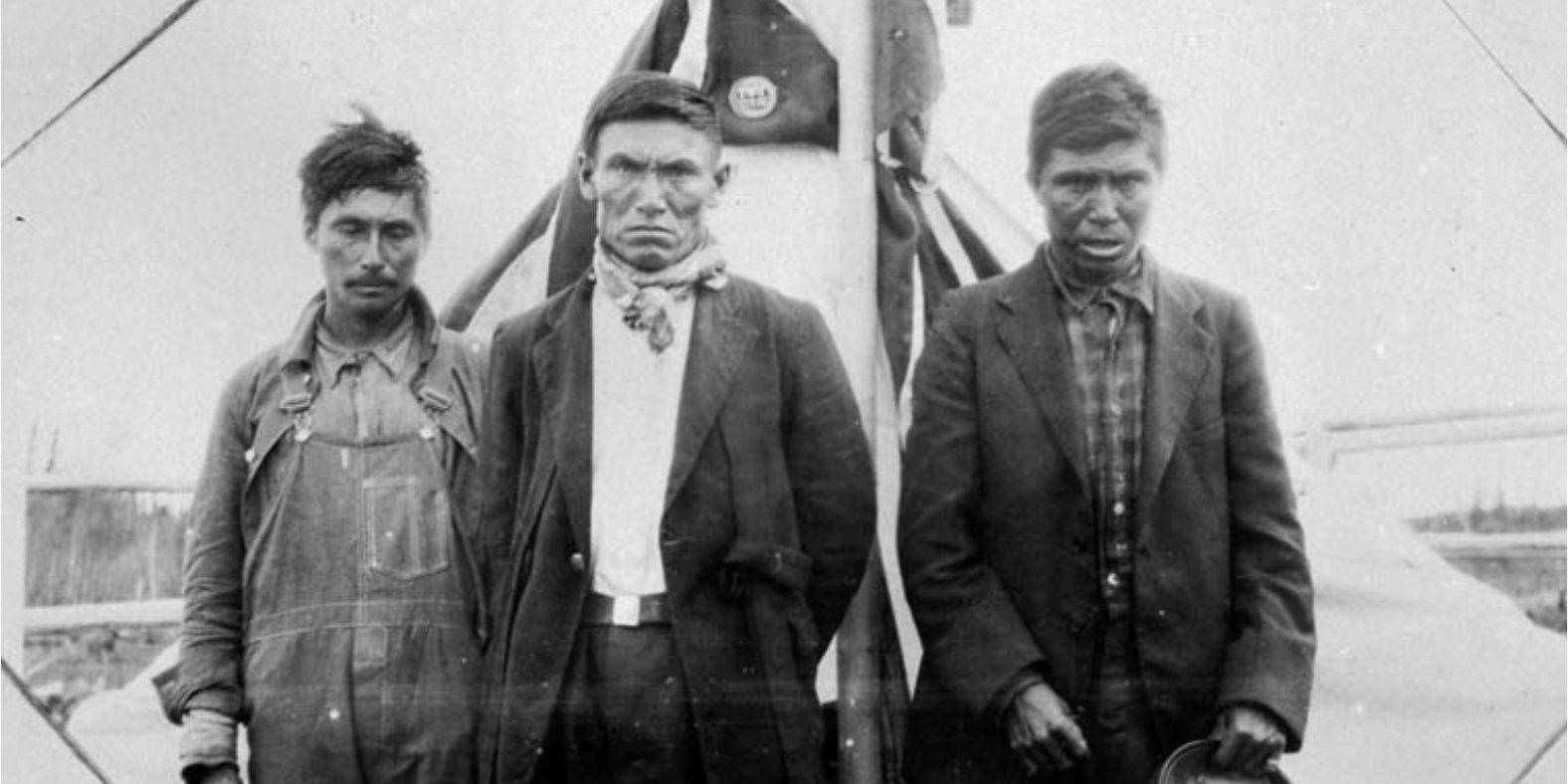

Featured photo: Councillor Samuel Sawanis, Chief Apin Ka-Ke-pe-ness and Councillor Senia Sak-che-ka-pow of the Caribou Lake Band, the first elected leaders of the band in Treaty. Photo: Canada. Dept. of Indian Affairs and Northern Development / Library and Archives Canada / c068948

Indigenous Canadians earn about 70 cents for every dollar made by non-Indigenous Canadians, according to Canada's income data. This is a very...

June is National Aboriginal History Month, and this year, the day after National Aboriginal History Month ends activities for Canada 150 begin....

We identify ourselves in many ways - by gender, generation, ethnicity, culture, religion, profession/employment, nationality, locality, language,...